Justice Department Steps Up Ferguson Involvement

August 15, 2014

Space history made as Europe’s Rosetta becomes first probe to catch comet

August 15, 2014If you stumble or make mistakes when trying to speak a foreign language, spare a thought for Europe’s hapless politicians. Recently, the continent’s political masters have been slapped by a new form of satirical attack—Bad English Shaming. A viral-video sub-trend, Bad English Shaming sees public figures foolhardy enough to let their rusty English be recorded on camera getting mocked and mauled for their poor foreign language skills.

Exhibit A of the trend is an impassioned speech made this month by Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi. Supposedly, it was in English. Renzi’s speech is so halting and garbled it’s hard to understand what he’s actually talking about, though it contains occasional lucid but surreal gems as, “He invent the telephone to speaking about in the theatre.” Since then, clips of Renzi’s stumbling performance have gone viral. Together, the subtitled version above and this nattily sampled Rock and Roll take have got over 2 million hits between them.

Then there were Madrid Mayor Ana Botella’s attempts last year to sell her city as a contender for the Summer Olympics. Mayor Botella’s stilted, halting English made her a national laughing stock, a reputation she has since solidified through gaffe after gaffe. What is telling about the derision for Botella’s efforts is that, from a native speaker’s perspective, they don’t seem too bad. Sure, viewers have to contend with her awful, hokey delivery (“Madrid is FAAAAAN!”) and the tendency to slap a mystery “e” on the start of words, but she still puts the average Brit’s Paella ‘n’ chips Spanish to shame. In Spain, however, the speech seems to have half the nation holding their sides. Botella will probably be Ms. Café con Leche until the end of her days now.

I doubt she’ll speak English in public again, but for European public figures today, even that won’t necessarily spare you. In 2009, Germany’s then-foreign-minister Guido Westerwelle was lampooned just for refusing to answer a question in English. Admittedly, I see the point here. Westerwelle’s brief was international, and with his mixture of oiliness and awkwardness, his spikiness was always destined to attract notice.

There’s a striking connection between these three little spats: The ridicule all came not from native English speakers, but from the politicians’ own compatriots.

It has not been ever thus. Francois Mitterrand’s exceedingly brief 1986 foray into English at the Statue of Liberty’s centenary celebrations was widely taken as a badge of skillful statesmanship. Looking back a few decades further, it was once possible for Italian and French singers to make garbled English-sounding noises that passed among many of their monolingual listeners as the real thing, a style known as “singing in yogurt.” Meanwhile, British pop singers who wanted to succeed in Europe often had to translate their songs to have a hope of cracking the market.

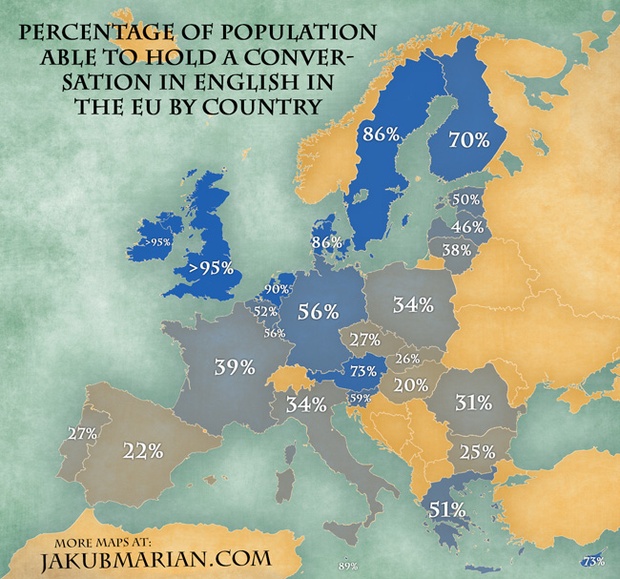

Clearly, something radical has changed. It probably isn’t the growth of American or British influence per se, as politically and culturally, these are either no greater than before or slightly on the wane. European English seems in fact to be uncoupling itself from native anglophones, a runaway caboose careering down its own track. The dominance of English as a European lingua franca is so total nowadays that it’s a basic tool for interaction even in countries where Brits and Americans rarely tread, as well as between Europe and other continents. This map shows just how far moderate English fluency has spread in Europe.

In countries where most people speak a Germanic language, at least 50 percent of the population can hold a conversation in English, as they can also in Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Malta, Greece, and Slovenia (and probably in other unlisted countries too). There’s still no shame in continental Europe attached to failing to understand broad British or North American regional accents, but many continental Europeans’ English skills are getting really good. So good, for example, that Scandinavian comedians can now make fun of British accents and count on a fully comprehending audience.

Once the number of English speakers tips over 50 percent, it seems people just get more demanding of each other. It’s one thing for a lazy Brit or American to complain about no one speaking English in Paris (though this happens less and less), but it’s quite another for a Dutch person to complain of the same thing—they’re already making an effort themselves. Like a bachelor’s degree and a clean criminal record, decent English is becoming one of those basic things you need to forge a career in Europe, political or not.

This may be good for native English speakers, at least given their relative reluctance to learn another tongue, but I feel for my European neighbors. If anything could move me to sympathize with continental Europe’s political elite, it’s the thought of someone waiting to be filmed under blazing lights, frantically trying to remember the rules of the past progressive tense.