Utah Jazz: Italian coach Ettore Messina among team’s candidates

April 28, 2014

Poland looks to Pope John Paul II with new eyes as Russia stirs (+video)

April 28, 2014 I’ve just finished reading Revolt on the Right, Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin’s fascinating book analysing the rise of Ukip and what makes the party and its voters tick. Mark Pack has already written a very good review for LibDemVoice here. Here’s my take on some of its key insights.

I’ve just finished reading Revolt on the Right, Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin’s fascinating book analysing the rise of Ukip and what makes the party and its voters tick. Mark Pack has already written a very good review for LibDemVoice here. Here’s my take on some of its key insights.

Who votes for Ukip? The ‘left behind’

For a start, it debunks the myth that Ukip is a party of disaffected, well-to-do, shire-Tories obsessed by Europe and upset by David Cameron’s mild social liberalism on same-sex marriage. Yes, there are some Ukip voters like that, but they tend to be its peripheral voters, the ones most likely to give the Tories a kick in the Euros next month then return to their traditional True Blue ways in time for the general election. Ukip’s core vote in reality is made up of what the authors define as ‘left behind’ voters, overwhelmingly comprising older white working class males with no formal educational qualifications.

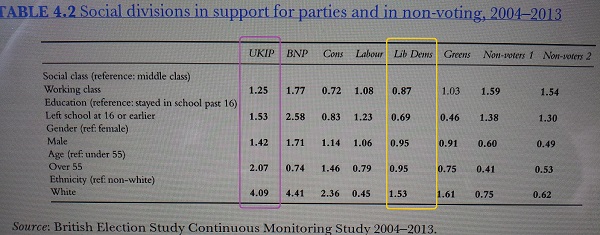

Here’s a table which illustrates this showing the social profile of voters among the main parties, including Ukip. (A figure of 1.25 means that group of voters is 25% more likely to support the party than the reference group; A figure of 0.25 would mean the named group is a quarter as likely to support the party as the reference group.)

As you can see, Ukip and the Lib Dems draw their voters from very different demographics: they are at opposite ends of the social spectrum, with Lib Dems more likely to be younger, non-white, female, middle-class and educated post-16.

Why do they vote for Ukip? Anti-Europe, anti-immigration, anti-Westminster and economically pessimistic

Secondly, the book looks at what issues motivate Ukip voters. There are two common assumptions of what defines a Ukip voter. Some say they’re obsessed by Europe, others say Europe is more or less an irrelevance and that Ukippers far more motivated by, for instance, immigration.

Ford and Goodwin’s assessment, based on extensive data-crunching, is more nuanced than either of those black-and-white conclusions. Deep Euroscepticism is, they say, a necessary condition of being a Ukip voter; but it is not sufficient in itself to win over converts (at least outside of Euro elections). Ukip persuadables are almost always Eurosceptics, but what turns them into active Ukip voters is when it combines with three other key concerns: being anti-immigration, discontented with the state of modern politics, and being economically pessimistic.

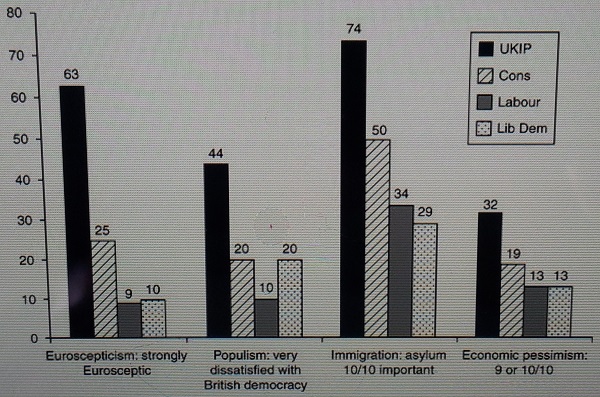

Here’s a chart from the book showing the proportion of each party’s support base expressing intense support (9/10 or 10/10) for their motive in supporting their chosen party.

It will come as no surprise to those people who read online comment threads or see Ukippers active on Twitter/Facebook to know quite how motivated they are: “angry, fed up and ready for a radical alternative,” as Ford and Goodwin put it. And that perhaps is the key to understanding why the Lib Dems have lost so many supporters to Ukip since the 2010 election – around 500,000 according to YouGov’s research. After all, the Lib Dems’ message has often focused on economic and political dissatisfaction with the established two parties, reaching its apogee (or nadir) with the party’s now-infamous ‘broken promises’ party election broadcast four years ago.

The moment the Lib Dems became part of the new Coalition Government, especially one implementing austerity economics, those voters attracted by its ‘none-of-the-above’ status quickly deserted it. In any case, a liberal party would always have had problems holding on to voters so strongly motivated both by anti-Europeanism and hostility to immigration.

What’s Ukip’s potential voter base? At least 30% of the public.

So Revolt on the Right explains who Ukip’s voters are (the ‘left behind’) and what motivates them (negativity about the current condition of the UK). What’s the potential for such a political party and which of the established parties is most likely to suffer from Ukip’s insurgency? Ford and Goodwin argue that Ukip’s recent rise is the result not of broadening their appeal, but of deepening it. Certainly that chimes with their current electoral strategy of targeting economically depressed areas with high numbers of pessimistic and disadvantaged voters – you won’t see Nigel Farage standing in a Conservative heartland like Buckingham next year, as he did in 2010 – and a resolutely negative platform of saying no to Europe, no to immigration, and no to anything that smacks of the liberal elite.

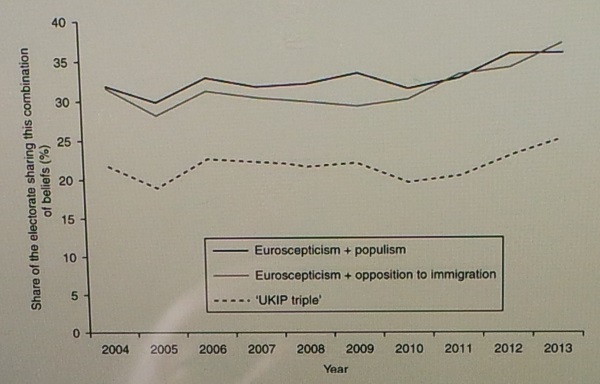

There is little here to appeal to moderate, progressive, centrist voters – but Ukip doesn’t care much about them and doesn’t necessarily need to. As the graph below shows, some 30 per cent of the electorate are both Eurosceptic and also opposed to immigration, or Eurosceptic and also politically dissatisfied, with around 20% combining all three: a Ukip triple whammy. That’s a substantial minority of voters who identify closely with core Ukip attitudes – and a growing minority, too.

Here, then, is the dilemma for both the Conservatives and Labour… A chunk of each of their core support among the Ukip-inclined demographic of ‘left behind’ voters is also highly sympathetic to these core Ukip attitudes. These voters are drifting towards Ukip as it establishes electoral credibility. Yet if either the Conservatives or Labour attempt to accommodate such views to hold onto those voters they risk falling between two stools, being seen as inauthentic by Ukip’s fervent fanbase while simultaneously antagonising the rest of their more mainstream voters. As a result, both parties are paralysed by how to respond to Ukip: should they denounce them (as David Cameron once did as “fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists”) or should they ignore them (as Ed Miliband has)? Only Nick Clegg has taken up a decisive position of taking Ukip on, assisted by the knowledge he’s not cutting himself off from his own voters.

Where is Ukip most likely to win? In Labour-held seats.

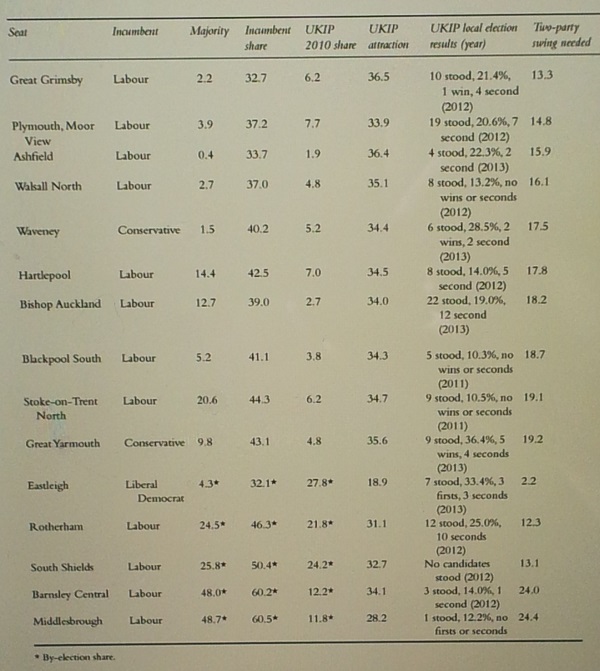

None of which means Ukip are assured success at the 2015 general election. Ukip suffers a problem quite familiar to third parties: their support is evenly distributed, not concentrated in enough constituencies to enable them to make a break through in the UK’s first-past-the-post system. Ford and Goodwin have drawn up a list of Ukip’s top 10

prospects based on seats with the most Ukip-friendly demographics where the current incumbent won last time with less than 45% of the vote (together with the five by-elections this parliament where Ukip has finished runners-up):

What’s striking about this list is how Labour-dominated it is: 12 of these 15 seats are currently Labour-held, two are Conservative and the Lib Dems hold Eastleigh, where Ukip came closest to winning its first MP 15 months ago. Yet to look at the list is to realise quite how formidable is the challenge facing the Faragistas in 2015; while it would be foolish to rule out the chance of Ukip snatching one of these seats it still remains more likely they will end up empty-handed.

If that happens, what then of Ukip’s disaffected voters? Would such an injustice fire them up for a bigger and better challenge at the 2020 election; or would a crushing disappointment trigger the kind of internal civil war that has previously so damaged Ukip inbetween their blazing Euro election eruptions? Who knows.

Can Ukip be an SDP of the radical right? Lose the battle but win the war…

There is one duff note in Revolt on the Right. Ford and Goodwin glibly dismiss the 1980s’ insurgence of the ‘radical centre’ when the SDP, albeit briefly, looked poised to win the popular vote: “in the end the SDP fell flat, barely denting the mould on the party system they had set out to break”. Except, of course, that the SDP lost the battle but won the war: Tony Blair’s victory under the New Labour banner in 1997 was, in reality, the SDP’s triumph. Socialism had been abandoned, and it was social democracy that propelled Labour to its biggest ever election victory.

Ukip may yet fail as an electoral force: it is, after all, hard to imagine a party reliant on the votes of a declining demographic of older, white, working-class, non-graduate men surging to victory. But that doesn’t mean they can’t win, just as the SDP did a generation before. It’s not so hard to imagine the Tories fighting an election in 2020 with a leader championing Better Off Out anti-Europeanism and decrying immigration. That’s the real danger Ukip poses.

* Stephen Tall is Co-Editor of Liberal Democrat Voice, and editor of the 2013 publication, The Coalition and Beyond: Liberal Reforms for the Decade Ahead. He is also a Research Associate for the liberal think-tank CentreForum and writes at his own site, The Collected Stephen Tall.