Union’s priceless history of togetherness with Scotland

September 15, 2014

Immigrants aren’t stealing your jobs

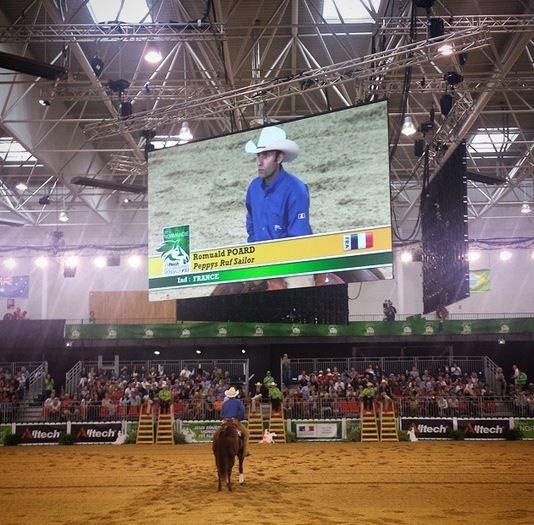

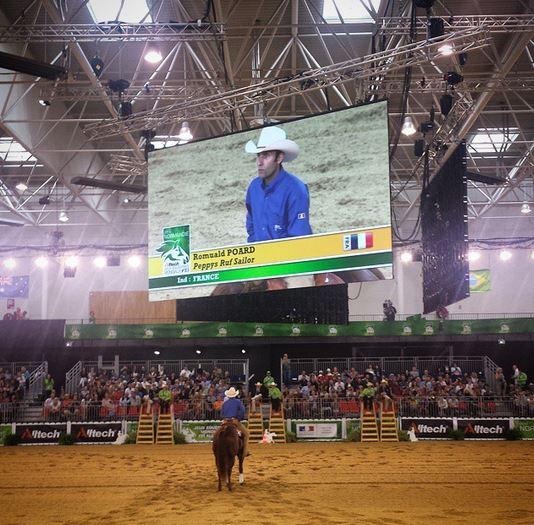

September 15, 2014For two weeks in late August and early September, the 2014 Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games controlled the spotlight in Normandy, France. Held every four years, the Games celebrate the worldwide traditions of a sport that dates back to the Olympic Games of 776 BC. Events such as dressage, jumping, endurance, and reining are performed on their grandest stage, showcasing horses worth upwards of $10M. On the whim of a pitch e-mail touting a place where “sidelines and beer are substituted for green fields and champagne, and the competing athletes reign from some of the world’s most powerful and royal families,” I attended the event. It sounded dope. It would be dope. So, as I stepped off the plane and drove past Paris and deep into the French countryside, I expected to arrive at a sort of secret society event, rubbing shoulders with the financial elites of the world and drinking endlessly free wine.

Instead, I was greeted by Shania Twain. And Avicii. And the guy who does that song, “Bad to the Bone.” All of them blared through the speakers of the Caen Exhibition Center, where the first event of my trip was taking place. Eventually, AC/DC’s “Highway to Hell” switched on and Bon Scott’s sharp, fuzzy growl roared over power chords and a backbeat thundering underneath. Metals bleachers were topped up with charged, rowdy fans. On the riding surface just below them, dirt that looked like a mixture of sawdust and sand was being kicked in the air. I had never seen more cowboy hats in my life. This wasn’t Normandy. This was closer to Paris, Texas.

The sport at hand was reining, a Western style of horse riding that originated in the United States over a century ago but was first recognized as a sport in 1949. In 2002, the World Equestrian Games added it as a category to the festival, a move that garnered a greater American interest for the Games and made the event more accessible to North American audiences. Riders compete to guide their horse through a series of movements with subtle and hypnotic precision. Spins and sudden stops are judged for their effortlessness. The relationship between the rider and the ride should seem natural. Cowboy-ish in nature, the event is directly tied to the Western folklore of John Wayne and Buffalo Bill. A member of the Canadian reining team spoke to me about his love for Marlboro Men and all those old dude ranch films we see less and less of on TV. Again, I was in France, the place where American exceptionalism presumably goes to die, and a Canadian man was telling me about his love for 10-gallon hats and horses. It was the first time I had ever seen a Frenchman in a cowboy hat. I’d be willing to bet it was also the last.

Reining has been a sort of “in” for American riders at the World Equestrian Games, as the U.S. typically fares well in the event. This year, Americans swept the individual reining event and took the gold in the team competition. The American silver medalist, Andrea Fappani, is generally regarded as the best reiner in the world. Born and raised in Italy, Fappani made the decision to train in the United States when he was 18, and he eventually became the National Reining Horse Association’s youngest-ever Million-Dollar Rider. In conversation, however, Fappani’s personality is quiet and confident. He is about as humble as you expect the son of an Italian dairy farmer to be.

“The harder you work, the more chances you get,” Fappani said of his success. His tone is matter-of-fact. “I’ve been very lucky.”

Reining might not have been flooded with the bubbly and bluebloods I expected, but the rest of the festival was a luxurious, global affair. In 2014, 74 different countries were represented at the Games, and 15 of them medalled. Zara Phillips, granddaughter to the Queen of England, rode in a series of events throughout the weekend, while Her Royal Highness Princess Haya of Jordan headed the Games as the president of the sport’s governing body, the International Federation for Equestrian Sports a.k.a. the FEI. Rolex and Land Rover served as the chief sponsors of the event, their names draped across tents and advertisements throughout the festival’s assorted sites.

In the events following reining, I sat in a VIP tent popping champagne with well-dressed attendants and reporters from across the world. Each morning, I was chauffeured to and from the festival grounds in either a Jaguar or a Mercedes. The blend of high and lowbrow culture was distinct, certainly unlike anything you can get from most sports in the United States, where oversized masculinity and beer ads rule the day. However, the FEI has been working to broaden the equestrian audience in the U.S., starting in 2010 when they brought the World Equestrian Games to Lexington, KY. The pairing was of paramount importance to the FEI; it brought the World Equestrian Games to its first location outside of Europe, and also wrangled Alltech, a title sponsor for the Games who is headquartered in Lexington. John Calipari was enlisted to promote ticket sales, nearly 420,000 visitors attended the event, and economic analysts reported a $201.5M impact on the state of Kentucky. It was, by various measures, a huge success. Yet, the FEI’s public profile in America remains small, particularly in comparison to domestic leagues like the NFL and the NBA. The FEI is looking to grow its sport, but how exactly are they going to do it?

The most prominent, modern success of basketball and football comes in a realm of media where equestrian sports are still looking to make a mark: digital media. Brands across the business spectrum are hungry for this type of content. Think about ESPN.com‘s recently-introduced “Instant Awesome” tab, or Madden‘s development of the “GIFerator.” These are blatant plays to devise quicker, more consumable information. Great plays like dunks and touchdown passes are best understood through relatively new mediums like GIFs and Vines, not text or spoken word. This is because they happen in seconds, not minutes. They don’t always need to be elongated. They’re a thing that should be easily embedded in a tweet, clicked, viewed, perhaps shared, and then stored away in the back of our minds.

How does a sport become viral? How does it catch on with a younger audience? These are questions that the FEI is focused on answering. In the United States, as the passive, sleepy appeal of baseball has given way to the high-flying or hard-hitting drama of basketball and football, it’s become a tricky question for sports leagues across the country. Baseball, with its war heroes and songs, was once considered the vanguard of purity in athletics. In the past 15 years, things have changed, as the sport has seen its widespread fanbase gradually dwindle and ratings for the World Series plummet. Essentially, it proves a fact that everyone already knew to be true: Nothing lasts forever.

These threats of irrelevancy loom large over every sport across the world, as we’ve come to an age where money and advertising are more joined with competition than ever. With their increasingly global appeal and high domestic viewership, the NFL and the NBA have groomed an understanding of success that is unprecedented. Here’s the gist of it: Sports leagues work better when they’re overwhelming us, not seducing us. You can impress someone in an instant, but finessing them takes time.

And this is the central problem of becoming a pastime: time. How much of it is an audience willing to give up? How much should they feel obligated to give to entertainment, particularly in the Internet age, when patience has become a luxury, and digestible, filling (if not completely fulfilling) content can be found everywhere you look? The NFL has been wildly successful at stealing their audience’s time. Aside from the gridiron theatrics, they’ve managed to make large, sexy events out of offseason combines, drafts, and exhibition games. Every occasion has its own intrigue. By now, the NFL has learned to sell water to whales. Eventually, it won’t be surprising if they find a way to make a three-day spectacle out of your fantasy football draft.

Meanwhile, baseball is a soft-spoken test in patience and sizing up your opponent. For a batter, a large part of your job is racking up pitch counts to induce wear and tear on the pitcher. It’s an invisible battle to incite fatigue. How do you make a highlight reel out of that? Home runs are nice, but they’re just one facet of a largely routine game. Double plays and field pop-ups are a matter of course in baseball. A batter will either hit the ball or they won’t. We can more or less take these details for granted. The same can’t be said for football or basketball, where each play or possession seems to offer variation—a web of different possibilities that spins to the same center but creates a dizzying number of paths in the process.

Maybe we lost the ability to wait out baseball’s slow-burn. Maybe the onslaught of 1-0 pitcher’s duels became too much for even a home run to save. But in a recent piece discussing baseball’s decline, the New Yorker’s Ben McGrath points out that, by the numbers, baseball is doing better than ever. Attendance and revenues are up. Instead of finances, the battle that baseball is facing is one of perception. How can a slow sport avoid sinking into the past?

Equestrian sports are up against that same sort of cultural struggle. It’s a connoisseur’s fascination. Despite its niche appeal, a sport that has literally been ruled over by barons, princes, and princesses is making a concerted effort to draw in a wider audience. It doesn’t have any of the American rags-to-riches fantasies that the NBA and NFL have famously produced. None that feel accessible to city populations, anyway, where the largest viewerships in the United States reside. After all, where is the closest stable to Brooklyn? Let’s also not forget the lack of commercial appeal the sport receives in comparison to basketball and football, which regularly host cultural heroes in court-side seats and stadium boxes. Off the top of my head, it’s difficult to think of any young, American icons who are known for their love of horses. Travi$ Scott rode horseback across the Texas countryside in his latest video, “Don’t Play”, which, admittedly, is an incredible song from an incredible mixtape. Kanye let us turn our gaze to white horses in the video for “Bound 2”. But I still don’t think you’ll see Complex Music publishing a list of the 15 Best Rapper-Horse Duos in History anytime soon.

However, like baseball, equestrian sports are trending upwards by the numbers, and advancements are being made in video production to make the sport more viewer-friendly. When the Games concluded on September 7, videos covering the event tallied more than 5.5M views on YouTube. Twelve nations made their World Equestrian Games debut. More than 1,000 hours of television were broadcast to countries across the globe.

“It’s expanding slowly, but I do think that there’s much more to come,” Princess Haya said. “The special thing about it is that it’s a traditional sport. But that doesn’t change the fact that we have to produce it in new, young ways. I think we should never lose sight of the fact that we should keep the tradition. I think many other sports sometimes lose the good parts they have by turning themselves inside out to sell.”

It’s also worth noting the changes that have been made to the actual competition, such as the freestyle dressage events, which recently started to incorporate music into their routines, creating a quirky and unexpected blend of horses and dancing. Yes, actual dancing. Hopefully it won’t be long before riders start adding Bobby Shmurda to their routine. Or Beyoncé, at the very least.

Realistic or not, format changes like this won’t hurt the sport, and any change to make the competitions faster and more spectacular will only help. Cricket, another ancient sport foreign to most United States viewers, is currently building a model for this type of reinvention. The sport’s recent introduction of the Twenty20 format has been a boon for its popularity, helping create a more athletic and dynamic version of a traditionally stodgy game. It’s been so viewer-friendly that ESPN recently decided to partner with cricket’s exclusive broadcaster, Willow TV, to bring the competition to ESPN3. A bright future for cricket in the United States isn’t completely far-fetched so long as it continues to have the Worldwide Leader on its side.

Maybe equestrian sports could see a similar trajectory in growth. Fappani was convinced in his belief of horse culture’s presence in the United States. When comparing the United States to his native Italy, Fappani said, “Horses are a huge part of American culture. There are a lot more people who understand horses.” Princess Haya echoed Fappani, stating, “I think reining has underpinned the fact that there are horses in so many different cultures. It’s amazing to go from the reining stadium to the dressage stadium to see the ways that horses have literally traveled through history.”

To the right eyes, the 2014 Alltech FEI World Equestrian Games showcase an artistic and historic sport. “In many ways, [riding horses] was a form of expression for me,” Princess Haya said. “I never used to like to speak. And that’s why I rode horses. They gave me my voice. They gave me, really, the best things in my life.” Those are big words coming from royalty. The only question is whether the FEI can get the rest of the world to believe what they see as true.

In the coming years, they’ll be doing it without the princess. In November, Princess Haya will step down as president of the FEI after eight years in the role, despite the fact that the FEI was willing to literally rewrite the rule book in order to keep her in office. Her replacement will not have a royal title, the first to do so in almost 60 years.

“This federation had always been led by someone with a title,” she said. “Not everybody, but it was definitely a way of thinking that this was a position for royalty.” But Princess Haya is confident that the best is still yet to come for the FEI and for the sport, despite the organization’s trepidations about her departure. “I do believe someone better than me will come. Every person has their time, and the times are changing.”

Gus Turner is a News Editor for Complex. He tweets here.