On Sunday, a Republican congressional cohort complained about the deal made to ensure the release of Prisoner of War Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl from Taliban captivity in Afghanistan. The politicians said that the deal put a price on the head of US soldiers with potentially deadly consequences.

They were almost right. The trade to free Bergdahl doesn’t quite put a price on the head of a US soldier — I can’t give you the cash value of a freed American POW. Rather, in Marxian terms, it tells us the exchange value: One American military life for five Guantanamo detainees.

The bellicose justice of war has long held enemy life as of lower worth than the lives of its own.

It took Marx much of the entire first chapter of Capital Volume I to delineate the technical differences between exchange value and price. Suffice it to say here, that it only makes sense to talk of prices when there is a market. Exchange values are simpler: At base, a commodity’s exchange value just represents the quantity of other commodities it can be exchanged for in a trade. There has been a trade, and, as such, a grim equivalence drawn between a captured American life and a captured un-American life (one-to-five).

?????

— June

?????

— June

According to reports, the five released detainees were flown to Doha where they were held in Qatari custody. These pictures show the Taliban detainees after they landed in Qatar.

But that’s not a market; the three-year long wrangle to secure the deal reflects that “five detainees” is not some going price for an American POW. This was a one-time only kind of deal with the offer available for a limited period only.

Civil libertarians have rightly bristled at the idea that Gitmo could be used as a point of leverage over human life. What sort of justice is reflected in a prison camp that holds detainees until they can be used in a deal? That question is not rhetorical. The answer, simply, is the justice of war (even a war as amorphous as that on Terror). This bellicose justice has long held enemy life as of lower worth than the lives of its own — it’s inherent in the othering required to call something “enemy.”

The purportedly dangerous five men will be released before any of the 78 Gitmo prisoners held without charge and already cleared for release.

News reports revealing the identities of the five Gitmo prisoners have emphasized that the detainees are all considered “senior” Taliban officials, with descriptors like “high-risk” and “high intelligence value” attached to their files. So, more specifically, Bergdahl’s exchange value is five high-level Gitmo detainees, five of “the enemy.”

These men were not among Gitmo’s 78 prisoners cleared for release. These five are among the 48 prisoners deemed ineligible for trial but too dangerous to release. Until the Bergdahl deal was struck, these were “indefinite detainees.” It is significant that as prisoners of war, these men, and Bergdahl, were subject to the logic of exchange, not the processes of justice. It was a deal, not a trial, that made the indefinite become definite in this instance.

The Taliban has no clue to whom it should return a captive US soldier. Read more here.

But if the release and transfer of these high-ranking Taliban operatives was achieved through the release of the only American POW believed to have been in captivity in Afghanistan, a dense shadow is cast (again) on the continued imprisonment of the 149 other inmates at Gitmo. The purportedly dangerous five men will be released before any of the 78 Gitmo prisoners held without charge and already cleared for release. It is wholly to his credit then that Sgt. Bergdahl’s father Robert used his current public platform to call for the release of other Gitmo prisoners. Taking to Twitter, the POW’s father wrote: “Ten years in Guantánamo: Tunisian families hope for loved ones’ release,” posting a video from the Guardian, in which family members lobby for the release of five Tunisians held at Guantanamo Bay.

Ten

— June

The elder Bergdahl, who awaits his son’s return to US soil, was battered with online abuse from Twitter users who saw his challenge to the exceptional disgrace of Gitmo as un-American. “You are an anti-American piece of shit,” one Twitter user told Bergdahl senior.

Certainly, if the American way is to abrogate international law and hold prisoners indefinitely, until a deal (not justice) is done, then Bergdahl’s appeal to greater justice is indeed highly un-American.

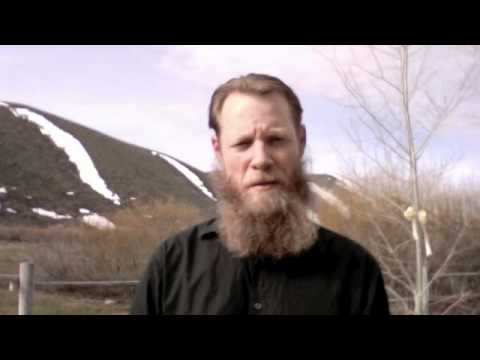

US soldier Bowe Bergdahl was released from captivity on May 31 having spent almost five years in captivity. This 2011 video shows Bergdahl’s father Robert making an appeal for his son. Video via YouTube/Robert Bergdahl.

Follow Natasha Lennard on Twitter: @natashalennard

Image via Flickr