Jáchym Topol’s Bohemian rhapsody draws on some dark moments of European …

June 6, 2014Recent vigour hides underlying weaknesses in Europe’s leading economy

June 7, 2014

AFTER months of procrastination, the European Central Bank acted on several fronts on June 5th to counter low inflation, currently just 0.5% in the euro zone. The ECB lowered its main lending rate from an already low 0.25% to 0.15%. More important, it became the first big central bank to resort to negative interest rates by lowering its deposit rate, paid to banks parking funds with it, from zero to minus 0.1%—in effect charging them. Moreover, it announced new measures to help credit-starved businesses in the periphery of the euro zone by providing cheap long-term funding to banks supporting such firms through their lending. Such stimulus had become essential to promote a broader recovery that relies less on Germany.

Buoyant German growth of 0.8% (or 3.3% at an annualised rate), reflected in Berlin by cranes on the skyline and roadworks at street level, was all that kept the economy of the euro area from contracting in the first quarter of 2014. Though that pace is likely to slow, Germany’s economy is expected to expand by around 2% a year in both 2014 and 2015, easily outstripping the rest of the single-currency club, as it has done since the euro crisis started in 2010.

Makers, not takers

Germany’s current-account surplus has averaged nearly 7% of GDP since 2006 and reached a new peak of 7.5% in 2013. Sustaining so big a surplus is all the more remarkable since Germany’s main export market, the rest of the euro zone, has been so sickly; the surplus with other euro members has fallen from 4.5% of GDP in 2007 to 2.1% in 2013. But exporters have been adaptable, taking advantage of the hunger in high-investing emerging markets for the machinery and transport goods that German firms excel at producing.

A humming labour market, helped by past far-reaching reforms, is another indication that things are going well. Employment last year reached nearly 42m, a rise of 3m in the past decade and the highest since unification in 1990. Unemployment has fallen from 11.4% of the labour force nine years ago to 5.2% now, a post-unification low and the second-lowest level in the 28-country EU.

The surge in jobs has contributed to healthy tax revenues. A long period of ultra-low long-term interest rates, in part due to Germany’s status as a haven during the euro crisis, has also lowered borrowing costs on government debt. These favourable conditions, along with fiscal restraint, mean that German public finances have been blooming, too. In 2012 the overall budget balance edged into surplus and last year government debt fell below 80% of GDP for the first time since 2009.

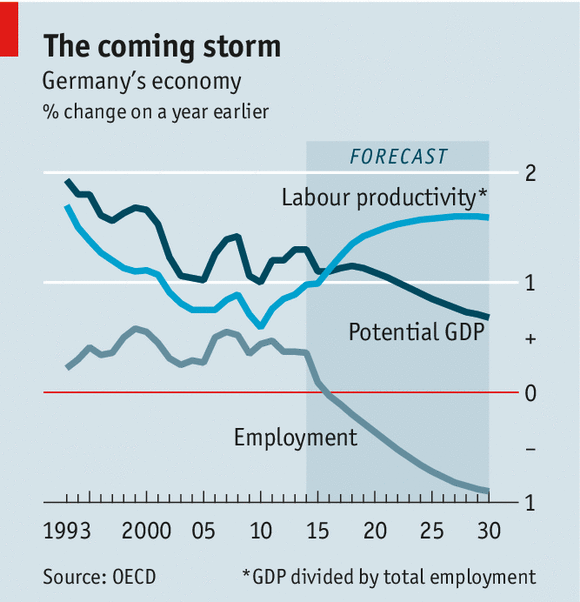

These economic and fiscal successes continue to make Germany a bastion of strength in the fragile euro zone. But the long-term outlook is worryingly weak. Although western Germany had a baby boom from the mid-1950s until the mid-1960s, its birth rate has been below the replacement rate (of around 2.1) since the start of the 1970s. Net migration, though currently high at around 400,000 people a year, will not be enough to counter this demographic drag, which is reducing the potential for growth by crimping the labour supply. That makes higher productivity growth vital. Yet even if productivity improves substantially, the demographic pressure is such that potential economic growth will fall below 1% within a decade, according to the OECD (see chart).

Raising productivity growth requires higher investment in both physical and human capital. Despite Germans’ pride in their imposing current-account surplus, it can be interpreted as a sign of weakness, since it represents a shortfall of domestic investment in relation to national saving. Total investment has fallen from 21.5% of GDP in 2000 to 17.2% in 2013. The government is not only investing too little in new infrastructure but also spending too little on maintenance.

The biggest decline in investment, however, has been from business. According to the DIW, an economic think-tank in Berlin, investment needs to be raised by around 3% of GDP permanently. Markus Kerber of the Federation of German Industry is especially worried about infrastructure, ranging from power grids to broadband.

The shortfall in capital is human as well as physical. In Berlin, as elsewhere in Germany, employers report skills shortages in many industries. Spending on education is lower than it is in other rich countries, with only part of that gap warranted by the dwindling number of children. An OECD survey of working-age adults in rich countries found that Germans were a little more numerate than the average but a bit less literate—a surprisingly poor result. The share of young people getting a tertiary qualification (such as a university degree) is less than a third, below the average for advanced countries.

Higher productivity growth will require a better performance on the part of the services sector, which makes up 69% of the economy. It lacks the dynamism of Germany’s manufacturers despite an encouraging surge in internet startups in Berlin. Reforms to enhance competition, especially among professional services, worth 10% of GDP, would help to gin up productivity more generally. The OECD advocates an array of reforms such as loosening the grip of notaries over commercial registration and the removal of regulated prices for the services of architects and building engineers—a restrictive arrangement unique to Germany within the EU.

But with things going so well, there is little appetite for a new wave of reforms. According to a recent poll by Eurobarometer, 84% of Germans are satisfied with the state of their economy, the highest share in the euro zone. The coalition government formed at the end of last year is too inclined to respond to the demand for payback after previous painful reforms, notes Michael Hüther, head of IW Köln, an economic think-tank. A case in point is the recent backpedalling on pension reform, which will allow some people to retire with a full pension at 63 rather than 65.

The resilience of the German economy should not be underestimated. But for the euro zone’s good and its own, Germany cannot afford to become complacent.