Judy Asks: How Can the European Parliament Strengthen EU Foreign Policy?

May 1, 2014

Muslim presence in Europe: ‘Talking to, not about, Islam’

May 1, 2014  i i

i i

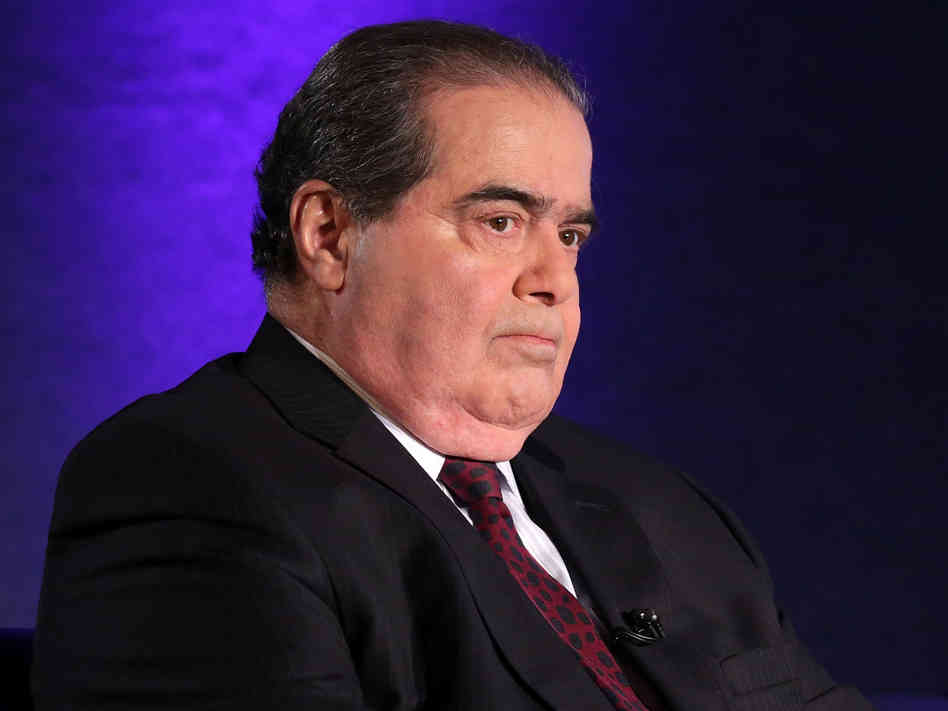

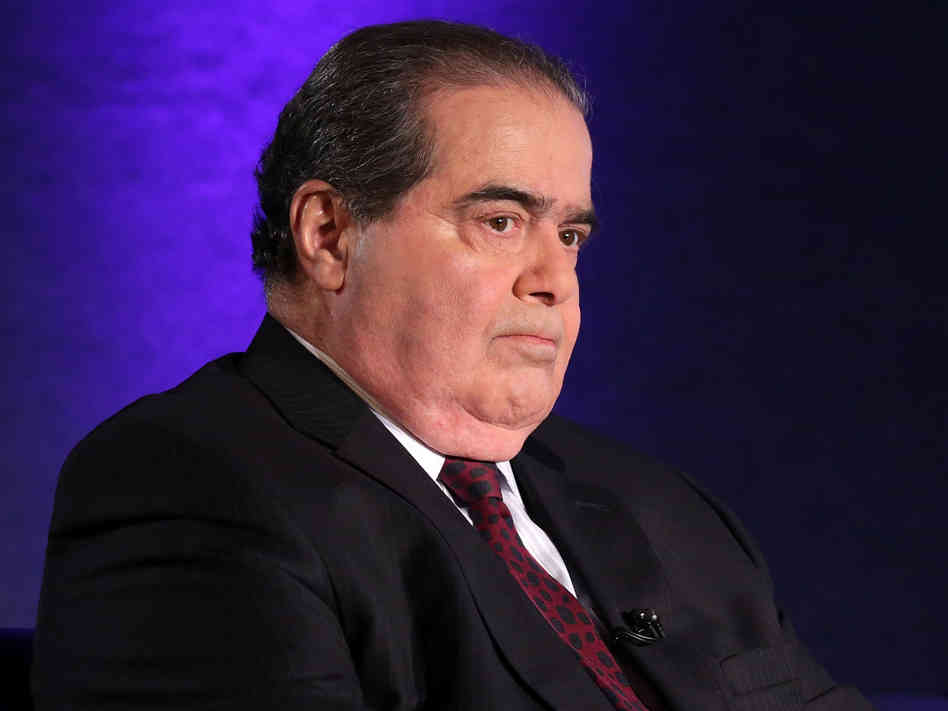

hide captionWhether the error in Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s recent dissent was originally his fault or a clerk’s doesn’t make it less cringeworthy.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Whether the error in Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s recent dissent was originally his fault or a clerk’s doesn’t make it less cringeworthy.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

All of us who write for a living know what it’s like to completely forget something you wrote 13 years ago.

But when a Supreme Court justice pointedly cites the facts in a decision he wrote, and gets them exactly wrong, it is more than embarrassing. It makes for headlines among the legal cognoscenti.

I’m not sure I rank as one of the cognoscenti, but here’s my headline for Justice Antonin Scalia’s booboo: “Nino’s No-No.”

The mistake has already been corrected on the Supreme Court’s website, but in the Scalia chambers, one suspects there is hell to pay. The justice has never made any secret of the fact that his law clerks write the first draft of his opinions, and then he rewrites them, putting his brilliant rhetorical stamp on the final product.

So, either the first-draft clerk got it wrong and Scalia didn’t catch it, or the justice got it wrong and the law clerk didn’t catch it. Either way, since clerks are first and foremost supposed to be a justice’s backstop, somebody is — to put it in delicate terms — likely having anatomical changes made to his or her body.

Here’s what happened. On Tuesday, the Supreme Court announced its 6-to-2 decision upholding the Environmental Protection Agency’s regulations governing power plant emissions that blow pollution across state lines.

Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, dissented, and he took the unusual step of announcing his disagreement from the bench for emphasis.

His dissent rested in large part on his contention that the Clean Air Act does not allow the EPA to use a cost-benefit analysis in setting cross-state anti-pollution regulations. And he cited as authority his own 2001 majority opinion for a unanimous court in Whitman v. American Trucking Assns., Inc.

“This is not the first time the EPA has sought to convert the Clean Air Act into a mandate for cost-effective regulation,” Scalia wrote Tuesday. The court’s 2001 Whitman ruling “confronted EPA’s contention that it could consider costs in setting NAAQs [National Ambient Air Quality Standards],” he said. And just as the court in 2001 rejected the EPA’s attempt to “smuggle” cost-benefit analysis into the statute, it should do so now, he argued.

The problem is that the EPA position was exactly the opposite in that 2001 case. The agency maintained that it did not have to consider costs in setting regulations, and it was industry — the trucking association — that wanted costs to be considered. Moreover, the issue involved a different part of the Clean Air Act.

Bottom line: Scalia inverted the 2001 facts to support his 2014 dissenting argument.

The scholarly blogosphere was agog, calling it a “cringe-worthy” mistake, an “epic blunder,” a “mind blowing misstatement” of fact, and “hugely embarrassing.”

Scalia, and the court, moved quickly to correct the mistake. By Wednesday morning, the wording and the subhead of the passage had been changed. Where the subhead used to say, “Plus Ça Change: EPA’s Continuing Quest for Cost-Benefit Authority,” it now reads, “Our Precedent.”

All I can say is that I pray my editors are a better backstop for me than Scalia’s clerks were for him.