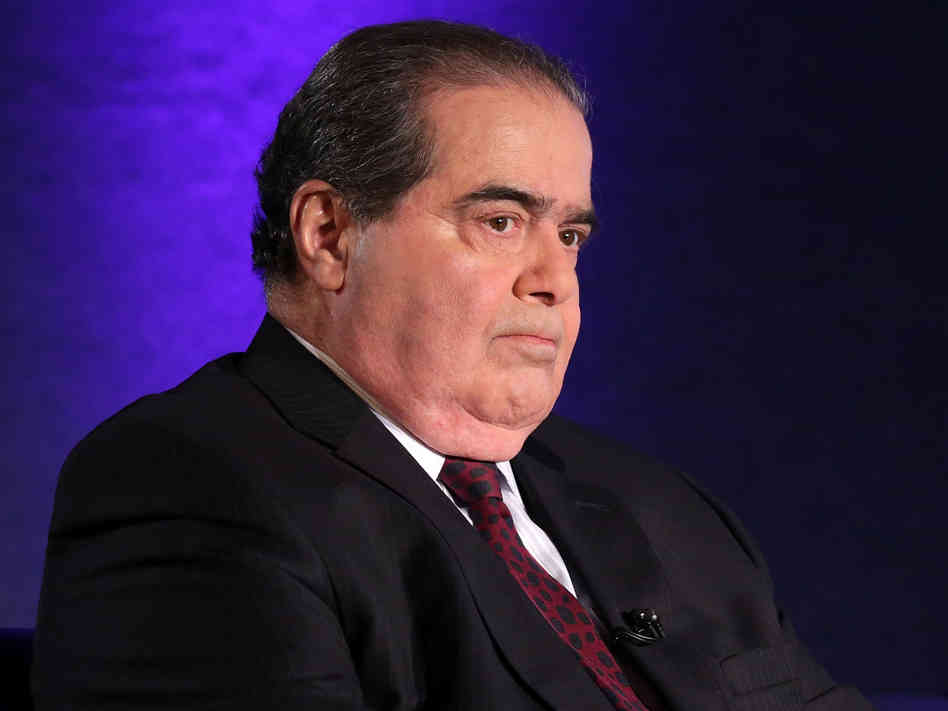

Nino’s No-No: Justice Scalia Flubs Dissent In Pollution Case

May 1, 2014

Copa America moving north for its Centenario? The perks of being a soccer fan …

May 1, 2014

28 April 2014

In his book, Inventing Europe, Gerard Delanty meticulously discusses how the idea of “Europe” and “Europeanness” has been reinvented throughout history. According to Delanty, Europe is more of a concept than a reality—a concept that has been envisioned several times throughout history. For instance, today, the Iberian Peninsula is seen as an inseparable part of Europe, whilst according to Napoleon “Europe begins at the Pyrenees.” For renowned historians like Halil nalck, Turkey is a founding actor of Europe. Yet Valery Giscard D’Estaing claims that “only five percent of Turkey” is part of Europe. These examples and many others indicate that rather than being an essential geographical or cultural entity, Europe exists mainly in the imagination, with its boundaries drawn according to perceptions. Unsurprisingly, as a result it has been “reinvented” throughout history.

The position of Muslims in Europe, one of the most discussed topics in terms of Europe and Europeanness, should also be viewed from this angle.

Europe’s collective imagination is now most preoccupied with the “immigration” phenomenon. The Muslim population’s increased visibility, combined with economic and social triggering factors, has sparked a wave of xenophobia based on the “Muslim Europe” rhetoric. The right-wing Norwegian extremist Breivik even killed 77 people in Norway in July 2011, in a massacre that won’t soon be forgotten in order to “create a consciousness to clean Europe of Muslims.”

During the investigation it came to light that Breivik had written a 1,500-page manifesto. The title of the manifesto was quite striking: 2083: A European Declaration of Independence. The Norwegian terrorist, projecting 400 years after the Ottoman Empire’s Siege of Vienna in 1683, states in his manifesto that his intention is to completely cleanse Europe of Muslims and thereby turn it back into a “Christian continent.” It is certain that Breivik committed a crime against humanity and his opinions are outliers among European thought: the overwhelming majority in Europe and the rest of the world strongly condemned his brutality. However, myths about the Muslim presence in Europe are part of a general phenomenon. And two of them deserve particular attention.

Beyond myths and exaggerations

The first myth about the Muslim presence in Europe is the proposition that Europe has been a “Christian continent” throughout history. However, as ener Aktürk indicates, this argument is not supported by history. If fact, Muslims have been in Europe for a long time. For instance, in the Iberian Peninsula, especially in Spain, Muslims were constitutive elements of administrative and social life from the eighth century until they were driven from the continent in 1492. Even today, Spain features deep traces of the Andalusian civilization. The same holds true for the Balkans. The Muslim presence in the Balkans has been an integral part of the region for centuries.

Similarly, the Jews, another one of Europe’s established heterodox religious groups, were collectively driven into exile from Europe at least four times; particularly in the age of industrialization, when the nation-state building and homogenization policies intensified. Of course, these cleansing practices were not particular to Europe. Yet, this does not undermine the point that depicting Europe as a “Christian continent” does injustice to the historical richness and diversity of the “old continent.”

The second myth, which has been linked to the first, is the argument that the Muslim population in Europe is increasing quickly and that Europe “will be invaded by Muslims” in the near future. In fact, Muslims—except for those in the Balkan countries—form a very small portion of the population in most European countries. Even in France, which has the highest proportion of Muslims, Muslims constitute only seven percent of the total population.

It is true that the number of Muslims in Europe is on the rise. As the native European fertility rate is lower compared to those who immigrate to the continent, the population ratio may change over the long term. Nevertheless, this trend should not also be over-exaggerated. According to PEW Research Center data, except for the Balkans, in 2030 the Muslim population will exceed 10 percent of the total population in only two European countries: France (10.3 per cent) and Belgium (10.2 per cent). Therefore, the “Muslim invasion of Europe” is not an accurate projection corroborated by robust empirical evidence but instead is a scapegoating tool exploited by far-right parties.

In summary, the claim that Europe has been historically Christian and will be exposed to a Muslim invasion in the future is not a reality but a myth. Europe’s real challenge for the 21st century is to strengthen multiculturalism. Europe owes its well-deserved success to the creation of a pluralist polity. Hence, she should maintain a hope for peaceful co-existence, not despair and alienation. As Patrick McCarthy puts it in a rather different context, for Europe, “the real goal is to live with and talk to, not about, Islam.”

This is a revised version of author’s article previously published in Analist monthly journal, October 2012 issue. The original version is published in Turkish and co-authored with Ouz Kaan Pehlivan.