A New Ambition for Europe: A Memo to the European Union Foreign Policy Chief

October 29, 2014

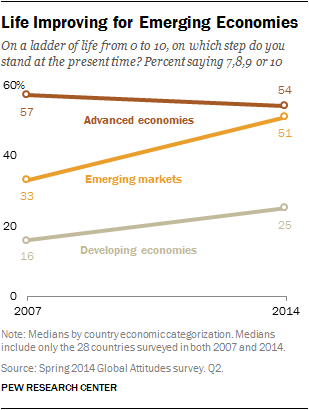

People in Emerging Markets Catch Up to Advanced Economies in Life Satisfaction

October 30, 2014

AT THE height of the protests in Ferguson in August, Dan McMullen, the owner of a local insurance company, was already thinking about the future. A grand jury trial weighing what happened the night that Darren Wilson, a white police officer, shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year old, had not even been convened yet. But Mr McMullen told The Economist he feared things would get worse if no one was indicted. He is not alone.

In the weeks and months since the riots erupted after Brown was fatally shot, a semblance of calm and order has returned to the St Louis suburb. Protesters were quieted by the launch of an official investigation and the prospect of an indictment for Mr Wilson. But leaks released last week from the grand jury trial, a supposedly secret procedure, suggest that an indictment looks unlikely.

The official autopsy report, obtained by the St Louis Post-Dispatch, indicates that Brown was shot at close range, which seems to support Mr Wilson’s assertion that Brown reached for his gun. It also seems to back up his testimony that Brown first ran from the vehicle, defying the officer’s command to stop, and then turned around and charged him. Brown’s blood was found on the gun, on Mr Wilson’s uniform as well as inside the car, which also supports Mr Wilson’s claim that the confrontation took place at short range and that he was acting in self-defense. Half a dozen witnesses also provided testimony supporting Mr Wilson’s view of the events.

Others, however, allege that Brown was shot with his hands up. Claims of Brown’s innocence—and Mr Wilson’s overreaction—are confirmed by a separate autopsy report, this one commissioned by Brown’s family.

The grand jury’s decision is expected to come down in a few weeks time. If the leaked evidence is representative of what the grand jury has heard, then Mr Wilson probably won’t be indicted. This will hardly soothe Missouri’s racial tensions. As one protester declared, “If there is no indictment, all hell is going to break loose.”

Local school officials are worried. The school year began a week late for local students, owing to the protests over the summer. To prevent more disruption, school officials have asked the county prosecutor to wait until classes are not in session—perhaps on a weekend or in the evening—before making the grand jury decision public.

Anticipating a furore, the St Louis County Police department has been reportedly stockpiling riot gear. The department has spent $173,000 since August on tear gas, plastic handcuffs, smoke grenades and canisters, rubber bullets, beanbag bullets and pepper balls. They have also invested in new helmets, batons and shields.

Besides amassing this new arsenal, the police department has undergone few changes since August. Some reports suggest that Ferguson’s police chief, Thomas Jackson, may soon step down as part of an effort to reform the department and place it under the management of the county police chief. It would be good if these reports prove true, as the county’s police department has a better record than Ferguson’s when it comes to managing crime. And a change at the top should help to reduce tensions between officers and citizens. In New Jersey nearly two years ago, a newly created county police force took over policing in Camden, a city plagued with crime. Since then nonviolent crime has plummeted. Rapes and murders have fallen too.

Yet Mr Jackson may not leave quietly. He says he intends to “see this through”. But he may not have much choice. The federal Justice Department is now investigating his leadership as well as police practices in Ferguson, including its use of force, stops, searches and arrests. The ACLU is also looking into the police department’s harassment of journalists who covered the protests. Many were detained illegally. Mr Jackson’s removal would go a long way towards restoring trust, not only in the police department but also in the justice system.

But without an indictment for Mr Wilson, many in Ferguson will believe there has been no justice. Ferguson residents, particularly its black residents, have long felt harassed by the police and mistreated by the courts. Many are sceptical that Robert McCulloch, the prosecuting attorney, is the right man for the job. He hardly allayed these concerns when he declined to recommend any charges to the grand jury. Instead, the jury will have to make sense of the evidence without guidance. But complaints that this reveals prejudice—and portends a miscarriage of justice—seem misguided, particularly as the jury is comprised of local Missouri citizens (three of the 12 members are black). Others argue that a grand jury trial is too secret, and that Mr Wilson’s case should be “out in the open”. But in the absence of a murder charge, a grand jury must first determine if there is enough evidence for an indictment. That is how the system works for everyone.

In the interest of transparency, and to pre-empt criticism, Mr McCulloch has pledged to release transcripts from the grand-jury hearings. But will this make much of a difference? As the events of Ferguson make plain, the evidence that counts may only be the evidence that people want to see and hear. If Mr Wilson is not indicted, Ferguson residents will probably take to the streets to protest. As for Mr McMullen, whose insurance-business windows were broken by looters in August, he says he plans to stay at home.