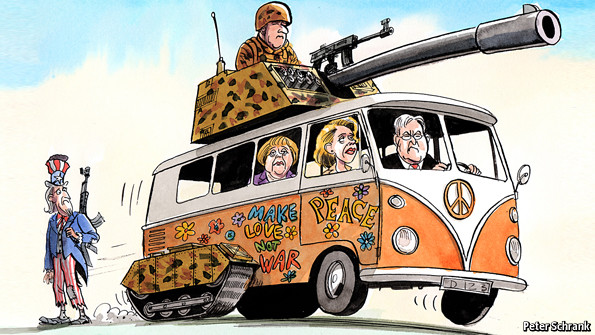

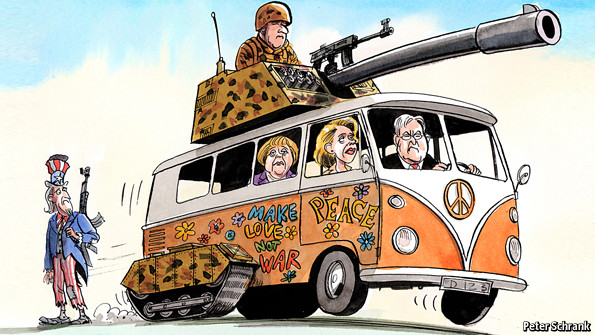

SINCE the second world war, Germany has farmed out foreign policy to America, France and Britain, its key allies, while refraining from playing a serious part in military missions in the name of pacifism. Only between 1998 and 2005 did Gerhard Schröder, then chancellor, and his foreign minister, Joschka Fischer, give a glimpse of a more muscular Germany, for example by sending troops to the Balkans. Under Mr Schröder’s successor, Angela Merkel, Germany has reverted to form. Guido Westerwelle, her foreign minister from 2009 to 2013, called this a “culture of restraint”.

Yet to its allies such restraint has increasingly made Germany seem like “the shirker in the international community”, as Joachim Gauck, the German president, put it in a speech to the Munich security conference on January 31st. The German diplomatic elite has long felt the growing frustration in Washington, Paris and London that Germany was not doing its fair share. There was particular anger over its refusal to back the 2011 UN Security Council resolution authorising war in Libya.

Mr Gauck, who has no policymaking power but speaks as the conscience of the country, is now urging Germans to step forward. He co-ordinated his speech with Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who succeeded Mr Westerwelle as foreign minister in December, having held the office in Mrs Merkel’s first term from 2005 to 2009. Ursula von der Leyen, Germany’s new defence minister and a possible future candidate for chancellor, has also come out in favour of a more active Germany. So, more cautiously, has Norbert Röttgen, head of the foreign-affairs committee in the Bundestag.

Only Mrs Merkel herself has not made her own views clear on this shifting consensus. This is her wont: she lets others float new ideas to observe how the debate unfolds, tipping the balance only at a late stage. But it is inconceivable that she would have allowed two of her ministers to forge ahead so far if she did not sympathise fundamentally with their point of view.

What do the diplomats mean when they now promise “more engagement”? Mr Steinmeier’s first objective is to repatriate to the foreign ministry the main responsibility for managing relations with the European Union, which migrated to the finance ministry during the darkest days of the euro crisis. He has made a start by hiring Martin Kotthaus, formerly a spokesman for Wolfgang Schäuble, the finance minister.

Mr Steinmeier wants to improve co-operation with France, not just over the EU but elsewhere. The implied quid pro quo is that Germany will more actively support France in Africa and France will back Germany in leading the EU’s policies in eastern Europe, says a foreign-ministry official. This gives Germany a tricky test right away in Ukraine (see article). But Mr Steinmeier also seeks non-military ways to be a better international partner. He feels, for example, that Germany should offer to dispose of Syrian chemical weapons because it has a suitable facility, even if Germans are uncomfortable with the idea.

Mrs von der Leyen is in principle ready to go further: towards a more unified European security policy, in which Germany would play a prominent role. Because this is at best a remote possibility, however, she is first trying simply to remove the domestic stigma from German military actions. Germany has about 5,000 soldiers in 13 missions worldwide, all playing a supporting role to allied troops. When NATO leaves Afghanistan, German soldiers are likely to be among the small number of Western troops that stay on.

Yet Mrs von der Leyen’s concrete proposals seem almost trivial. In Mali, where the French are fighting against a jihadist takeover, she wants to raise the number of German military trainers from about 100 to perhaps 250. In the Central African Republic, where French troops are trying to stop bloody clashes between Muslims and Christians, Mrs von der Leyen would send aircraft to fly out the injured.

Those African missions are strategic sideshows to Germany’s real national interests, says Ulrich Speck at Carnegie Europe, a think-tank. Germany should worry more about rebalancing its relations with Asia, where for economic reasons it has recently favoured China while neglecting South-East Asia and Japan. And it should force the EU to come up with a coherent stance toward Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

Nonetheless, the new signals from Germany’s elite amount to a big change. They are based on the perception that America cannot or will not be around, as it once was, to solve Europe’s problems in future. Since revelations of American spying on Germans began last summer—the latest discovery is that America tapped not only Mrs Merkel’s phone but also Mr Schröder’s since 2002—trust in the former protector has been damaged, although Mr Steinmeier and Mrs von der Leyen are both keen to limit a further rift. More generally, the debate reflects a new self-confidence in Germany. After atoning for its sins for 69 years, the country is now “a good Germany, the best we’ve ever known”, as Mr Gauck puts it.

The biggest hurdle remains public opinion at home. A new poll finds 62% of Germans opposing Mrs von der Leyen’s ideas about making the German army more active abroad. Mr Steinmeier therefore plans to spend this year touring not only the world but also Germany to convince voters that the time has come to reconsider their reflexive and often moralising pacifism. “While there are genuine pacifists in Germany, there are also people who use Germany’s past guilt as a shield for laziness or a desire to disengage from the world,” Mr Gauck said in Munich. Even on the political left, which still looks askance at NATO and sometimes the EU, such attitudes are becoming harder to defend.