The latest report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is out, with its layers of deadening bureaucratic prose. Climate watchers have had their latest chance to make out, as best they can, what biblical futures await us on a hotter, drier, stormier planet. Two sentences from the report’s second installment struck me with the force of a storm surge: “Climate change is projected to progressively increase inter-annual variability of crop yields in many regions. These projected impacts will occur in the context of rapidly rising crop demand.” Translation: We’ll have smaller harvests in the future, less food, and 3 billion more mouths to feed.

The IPCC has done an heroic job of digesting thousands of scientific papers into a bullet-point description of how global warming is shrinking food and water supplies, most drastically for the poorest of Earth’s 7 billion human inhabitants. Being scientists, though, they fail miserably to communicate the gravity of the situation. The IPPC language, at its most vivid, talks of chronic “poverty traps” and “hunger hotspots” as the 21st century unfolds. The report offers not a single graspable image of what our future might actually look like when entire populations of people—not only marginalized sub-groups—face perennial food insecurity and act to save themselves. What decisions do human communities make en masse in the face of total environmental collapse? There are no scientific papers to tell us this, so we must look to history instead for clues to our dystopian future.

The last global climate crisis for which we have substantial historical records began 199 years ago this month, in April 1815, when the eruption of Mt. Tambora in Indonesia cooled the Earth and triggered drastic disruptions of major weather systems worldwide. Extreme volcanic weather—droughts, floods, storms—gripped the globe for three full years after the eruption.

In the Tambora period from 1815 to 1818, the global human community consisted mostly of subsistence farmers, who were critically vulnerable to sustained climate deterioration. The occasional crop failure was part of life, but when relentless bad weather ruined harvests for two and then three years running, extraordinary, world-changing things started to happen. The magnitude and variety of human suffering in the years 1815 to 1818 are in one sense incalculable, but three continental-scale consequences stand out amid the misery: slavery, refugeeism, and the failure of states.

Across what was then the Dutch East Indies, the rice crop failed for multiple years following Tambora’s eruption. In response, the common people did what they always did when faced with starvation: They sold themselves into slavery, by the tens of thousands. In faraway China, desperate parents likewise sold their children in pop-up slave markets.

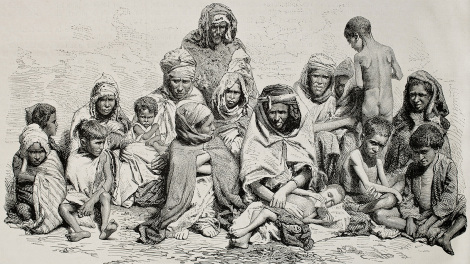

Across the globe, starving peasants abandoned their homes, roaming the countryside in search of food, or begging in the market towns. Irish famine refugees, numbering in the tens of thousands, were met by armed militias at the gates of towns whose inhabitants feared a kind of zombie invasion by human skeletons carrying disease. In France, tourists mistook beggars on the road for armies on the march.

Meanwhile, governments everywhere feared rebellion, so they closed borders and shut down the press. Europe witnessed an upsurge of end-of-the-world cults. In southwest China, Yunnan province suffered total civic breakdown post-Tambora, only to remake itself as a rogue narco-state, new hub of the booming international opium trade.

These are the sorts of world-altering disaster scenarios the IPCC’s board of scientist-bureaucrats fail to mention in their latest report. But then, climate change has never had its own proper language, a language commensurate with the threat it represents, a language that would forcefully express what it is: the great humanitarian crisis of the 21st century.

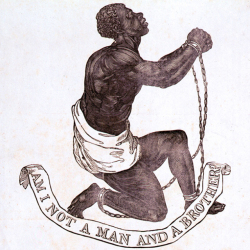

To invent a language for climate change, we might start with the historical analogy of slavery, which flourished during the Tambora climate emergency two centuries ago. Like our future under climate change, slavery was a human-designed global tragedy that lasted centuries, displaced tens of millions of people, and reorganized the wealth and demographics of the planet. Like climate change, slavery institutionalized the suffering of millions of people from the global south so that folks in Europe and North America (and China) might lead more comfortable, fulfilling lives. And like climate change, few people at the time saw slavery as a serious problem. Even those who did believed nothing could be done without bringing about global economic ruin. That exact argument is used today to defend the continuation of our fossil-fuelled societies.

Some historians have argued that it was the harnessing of carbon energy—not the abolitionists—that truly made an end to slavery possible in the 19th century. But in a dark historical irony, that same carbon energy, as a pollutant altering the chemistry of the atmosphere and oceans, is now ushering in a new era of global slavery. Millions this century, living and yet unborn, face displaced lives without hope or freedom of choice, only desperate hardship, due to haywire changes in weather patterns.

Does that make climate change the new slavery? One thing we can say with “high confidence,” to use the lingo of the IPCC, is that even now—as the U.N. panel marks its quarter-century anniversary with its fifth and most dire report—there is no international climate change movement comparable to abolitionism. For one thing, we don’t even have a name for the millions of people across the world who are passionately committed to the cause of averting climate disaster. Even Bill McKibben, probably the most effective climate activist in the United States, when branding his organization, could do no better than a number—350, the parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere we need to return to for climate safety.

Given that climate activism is faring so badly in the public-relations stakes, perhaps it’s time to brush off the old slogan that worked so famously well for the abolitionists, the rallying cry of the greatest humanitarian victory of all time: “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” And instead of an African in chains above the caption, let’s show a crowd of faces from Africa, Asia, the Pacific, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and the Arctic north—the faces you won’t find in the IPCC’s report, but who are stubbornly real nevertheless, living precariously in their millions on the shifting global frontlines of climate change.

Given that climate activism is faring so badly in the public-relations stakes, perhaps it’s time to brush off the old slogan that worked so famously well for the abolitionists, the rallying cry of the greatest humanitarian victory of all time: “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” And instead of an African in chains above the caption, let’s show a crowd of faces from Africa, Asia, the Pacific, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and the Arctic north—the faces you won’t find in the IPCC’s report, but who are stubbornly real nevertheless, living precariously in their millions on the shifting global frontlines of climate change.