Rabbitoh Tuqiri ready to fire

February 9, 2014

Renzi pressures Italian government to declare its lifespan

February 9, 2014A week doesn’t go by without hearing about the problems which will be created by the world’s rapidly aging population. Much of the focus is on how fewer people will mean lower future economic growth. The likes of Harry Dent have popularised the idea but it’s also been given intellectual heft by thousands of demographic consultants.

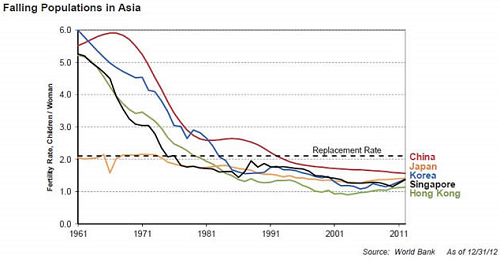

There’s no doubt that the world is getting older. Many will be surprised to learn that even Asia has serious issues on this front. For instance, fertility rates in South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore are below those of European countries such as Italy and Germany, which are most commonly associated with demographic problems.

The post today though will look at the silver linings associated with aging demographics. Older populations don’t necessarily equate to lower economic growth. Boosting productivity is the key to offsetting declining working-age populations. Without it, there will indeed be much lower growth but we’re hopeful that the seriousness of the issue will prompt real solutions to address productivity. Also, having fewer people in the future may end up being the best thing that could have happened to us. There’s considerable evidence that we’re now living in a resource-constrained world. One where we may soon face a food crisis as agricultural inventories dip to decade lows thanks to lower crop yields and increased demand from Asia. Fewer people should mean reduced resource consumption and may actually save us from not having enough food to feed the planet.

For investors, aging demographics and resource constraints do mean the odds favour slower economic growth in the decades ahead. Yet these issues will also create some tremendous investment opportunities in areas such as biotechnology, robotics, agriculture, and renewable energy.

Aging doesn’t equal lower growth

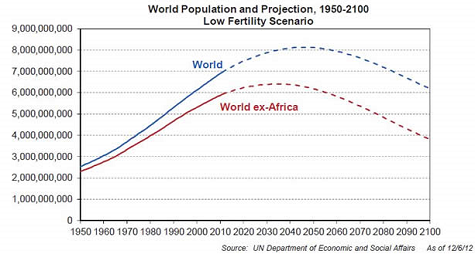

I’m not going to detail how the world is rapidly aging as it’s been done ad nauseam. Suffice to say that many don’t quite comprehend how quickly the process is taking place. For instance, many government agencies predict peak world population of around 8 billion by 2050. What’s more interesting is that much of the population growth will occur in Africa. Ex-Africa, the world’s population could peak around 6.5 billion as early as 2040. Below is the optimistic case as outlined by the U.N..

Let’s put that into context. I’m 38 years of age. Within my lifetime, I’m likely to witness a declining global population. Moreover, I may be reaching retirement age when the world population, ex-Africa, starts to fall. Unless, of course, our governments lift the retirement age to 80, which can’t be ruled out!

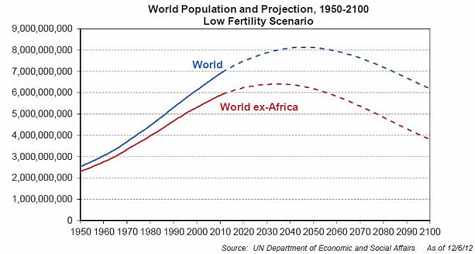

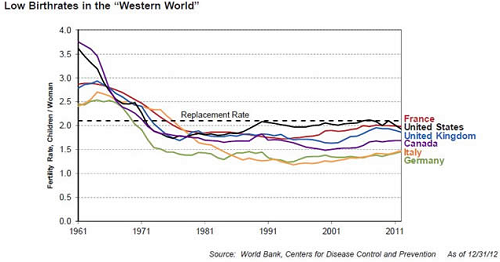

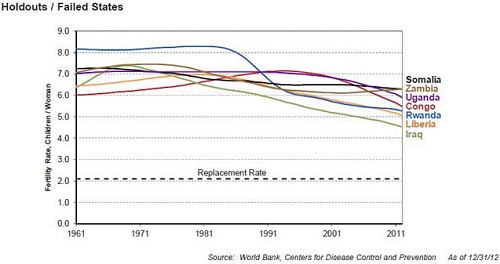

The key driver to slowing population growth is declining fertility rates. And the causes of these falling rates include advances in birth control and improved education of women. The numbers on fertility rates are staggering. It’s no surprise that many developed countries now have fertility rates well below so-called replacement rates, with Europe featuring prominently.

What’s less known is that Asia faces a similar predicament to the West. China’s birth rate has declined from 6 in the 1960s to 1.5 today. South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong all have birth rates among the lowest in the developed world. Even below the likes of Italy!

Africa and parts of the Middle East are the primary areas where fertility rates are well above replacement rates. Greater populations are the last thing that many of these areas need though.

Aging doesn’t equal lower growth

There’s a widespread assumption that an aging demographic profile invariably leads to lower economic growth. Japan is often held up as proof of this.

The assumption has several flaws:

- Historical experience suggests that you can have strong, above-trend economic growth in places where populations are aging. Venice in the 11th century and the Dutch Republic in the 14th century are prime examples.

- Modern-day experience also pokes some holes in the theory. If population alone led to stronger economic growth, then Africa today should be shooting the lights out. Only it isn’t.

- The underlying flaw is that population growth is only one-half of the GDP equation. GDP growth equals population growth plus productivity growth. You can have zero population growth and still be growing GDP via productivity enhancements.

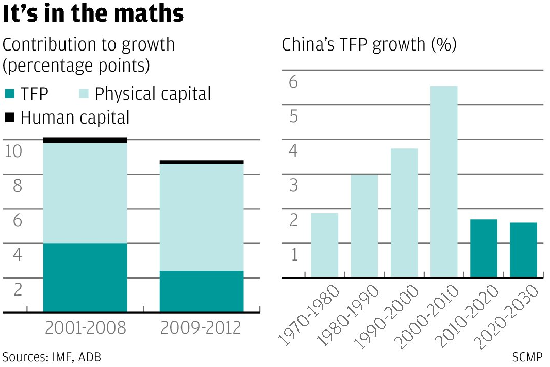

Of course, aging demographics make it more likely that a country will have slower economic growth. To explain this further, let’s look at a concrete example in China. South China Morning Post columnist, Tom Holland, had a good article on this over the past week. He explained the maths behind why China GDP growth should soon slow sharply to 6% or below. He first used an an analogy to explain GDP growth:

“If you run a sausage factory, there are three ways that you can increase the output of sausages. You can employ more staff to make them. You can invest in new sausage-making-machinery. Or you can use the staff and machines that you already have more efficiently.”

The first two factors are easy to measure but the third isn’t, and it’s referred to by economists as Total Factor Productivity, or TFP. China has some big issues. Its working-age population peaked in 2012. That means it has less people to make the proverbial sausages. It also has had a big drop-off in TFP in recent years. The country’s GDP growth has been held up by greater investment in physical capital. Or investment in new sausage-making machines, using Mr Holland’s analogy.

The problem is that the working-age population is set to decline further. And China wants to reduce investment in favour of consumption as the government has recognised that it’s been too reliant on the former. Consequently, investment could easily decline by one-third in future. It means China will need a big lift in TFP for GDP growth to be maintained at current levels. That seems improbable.

People forecasting 5% GDP growth in China in the near future are often referred to as extreme bears. But the maths suggest that it’s a pretty realistic scenario. In sum, an agiing population doesn’t directly correlate to slowing economic growth. But it makes it more likely.

Add resource constraints and there’s an issue

In my view, the other key issue in coming decades which receives much less attention is that of an increasingly resource-constrained world. It’s the combination of this and aging demographics which makes for increased odds for a slower growth world. Two weeks ago, I wrote a post reviewing a book called Life After Growth, discussing resources constraints. It received more comments than any other piece that I’ve ever written. There were lots of strong opinions, vested interests and plenty of believers in technology overcoming any future obstacles.

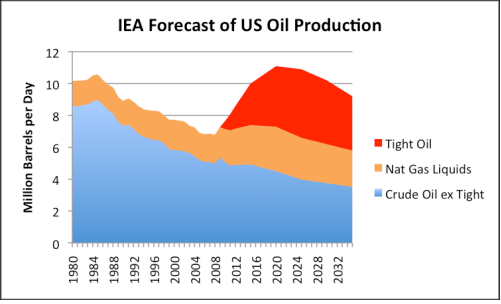

I won’t repeat the previous post but simply point out that there’s considerable evidence of resources being much harder to find and more costly. And in some cases, we’re just running out. In the case of oil for example, U.S. production from conventional sources peaked in the early 1980s. Since then, growth of unconventional sources has resulted in very modest growth in total oil production. Unconventional oil primarily means offshore drilling, which is much more costly. Not surprisingly, higher oil costs have resulted in elevated oil prices.

Yes, there’s all kinds of work into producing more oil via unconventional means. Tar sands and share oil are examples. The problem is that both of these are tremendously expensive and energy inefficient. In 20 years time, both may well be considered the Kodaks of the energy world (technology bypassed by better quality, low cost means). The likes of solar and wind power do offer some hope, though both are still too costly to compete with hydrocarbons, but that should change over the next few decades.

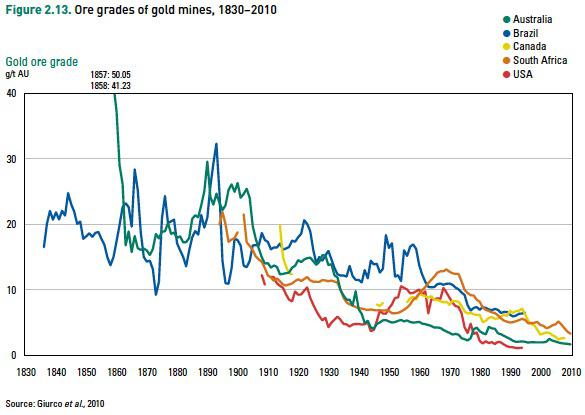

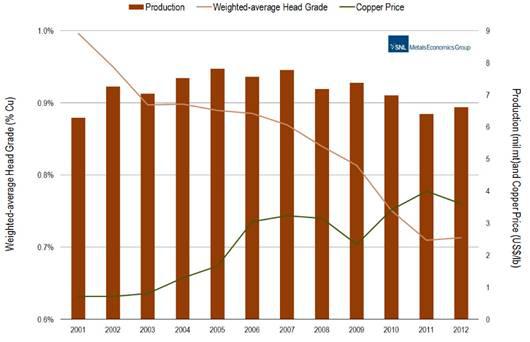

Regarding constrained resources, I’d also point to metal ore grades, which are rapidly declining in most cases. Take gold and copper as examples.

Declining grades mean they’re much harder to find and much more costly to bring to production.

Lastly, let’s look at agriculture, where perhaps the most acute shortages are present. The common assumption is that we have a lot of land available for agriculture. That’s true. But the issue is that the amount of prime agricultural land is declining. That’s resulting in reduced crop yield growth. Thus, crop yield growth has dropped from 3.5% per annum in the late 1960s to 1.25% now. The latter figure is still okay, of course. The issue is that it’s closing in on global population growth of 1%. Further falls in crops yields do not bode well!

You may ask what these resource constraints have to do with future economic growth. Well, as explained in my book review, cheap energy has been the principal driver for economic growth since 1750. If the era of cheap energy is over, then growth may be impacted too. And, no, technology is highly unlikely to save the day. Via the comments to my aforementioned book review, I was amazed by the number of people who had faith in technology to fix our energy issues and ultimately boost economic output. There’s little doubt that we live in an age of technological optimism.

But here are a few things that should trouble these optimists:

- Over the past two decades in the U.S., economic growth has slowed markedly from previous decades despite technological progress. Sorry, but Apple (AAPL) and Twitter (TWTR) don’t move the dial on economic productivity, with the latter reducing productivity if my experience is anything to go by.

- Technological improvements weren’t able to stop conventional oil production from peaking. Despite trillions of dollars in spending.

- Technology wasn’t able to prevent mining ore grades from deteriorating.

- And technology wasn’t able to stop crop yields from sharply declining.

The faith in technology to solve problems from aging demographics and resources constraints seems to be contrary to much of recent experience. That doesn’t mean it can’t happen but I wouldn’t bet on it.

The upside of aging

Right, the outlook appears fairly gloomy thus far. Where’s the bright side in all of this, you may ask? In my view, there are a couple of key silver linings to a world rapidly getting older:

- Over the next decade or two, the issue will reach a critical stage where politicians and policy makers will be forced to provide solid solutions to boost productivity and economic growth. Without these solutions, growth could fall to levels no one will like. In other words, a crisis is more likely to result in concrete action. Of course, skeptics will point to the 2008 credit crisis and the distinct lack of reform since as reason to doubt that real change will take place. And I’ve got a lot of sympathy for that view. However, the seriousness of the aging and resource constraint issues may end up dwarfing that of the recent credit crisis and I remain hopeful that will force change. And by change, I mean long-term investments in innovation, education and technology in order to lift economic productivity.

- Fewer people on the planet post-2050 may not be the disaster that many economists make it to be. In fact, it could be the best thing that could have happened. It may reduce resource consumption and alleviate some of the important concerns around food availability in future.

If we do get ground-breaking reform and a declining global population, then we may end up in a boring, slow growth world. But that mightn’t be a bad thing given the economic volatility of recent times. And more importantly, we’d have a much more sustainable growth model.

Investor takeaways

The key takeaways for investors from all of this are:

- You should prepare for a slower growth world. Aging demographics and resource constraints make it more likely than not.

- Parts of the the world’s fastest growing region, Asia, appear particularly vulnerable. That’s because favourable demographics and cheap resource extraction have provided significant tailwinds to economic growth of late. And those trends are set to reverse.

- Investment returns may be lower than in previous decades. Given this and the aging demographics, yields/dividends on assets should take on greater importance. In other words, the current search for yield may not be cyclical, but generational.

- You’d think the search for yield would create a natural demand for the safety of bonds, but given current pitifully low bond yields, that may not be the case.

- That could create sustained, long-term demand for the likes of commercial and industrial property. Residential property in most countries offers much lower yields than these other property segments and therefore won’t be as attractive.

- Yield in appreciating currencies will be important. Particularly given the current determination of central bankers to debauch their currencies. We prefer Asian currencies over the West given sounder balance sheets. On a long-term basis, we like the Chinese yuan (though not on short-term basis), as well as the Singapore and New Zealand dollars.

- Specifically on stocks, you should not only consider those with sustainable, strong yields but also look at how the potential for elevated resource prices may impact companies in your portfolio.

- There will also be significant investment opportunities in areas which provide solutions to some of problems of aging demographics and resource constraints. Robotics to improve work productivity, for example. Biotech to help us live (and work) longer. Healthcare technology which helps mitigate rising healthcare spending. And in agriculture and renewable energy as resources constraints become more urgent.