Construction of the European Extremely Large Telescope has officially begun in the Atacama desert in Chile, marking the first step in a true mega-project that could offer us answers to some of the most profound questions in science.

The event this week, the blasting of the top of Cerro Armazones – 3,000 metres high until Thursday, a few less now – was far less dramatic than many of the onlookers at the European Southern Observatory’s Paranal facility 25 kilometres away had hoped for, but it was a significant first step in taking the E-ELT from the drawing board to reality.

The function of the blast was to loosen many thousands of tonnes of rock from the summit in order for the earth movers to begin clearing a flat, circular area for the foundations of the telescope. This really is just the first small step in a massively ambitious project to build the E-ELT that will take at least a decade to finish.

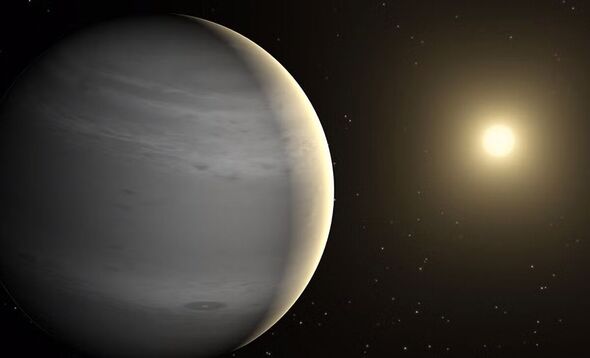

The science case for the E-ELT is quite easy to make, even to non-astronomers. While some of the great telescopes now in space and on the ground are designed to observe technical subjects such as the geometry of galaxies or the formation of stars, the E-ELT pitches itself as the telescope that will allow us to directly look at other planets around other stars.

The E-ELT science team reckon they have a good chance of being the first to directly observe little blue dots like Earth, if they exist.

But first, they have to build it, and doing so in the Atacama desert, one of the driest and most remote areas on Earth, is, in the words of ESO project manager Roberto Tamai, ‘a total nightmare’.

The first decision, taken quite some time ago, was which mountain to build the E-ELT on. There is no lack of bleak, windy, and lifeless peaks in the Atacama, so why Cerro Armazones in particular? They could have built it much closer to the ESO Paranal facility, home to the poetically named Very Large Telescope and the famous ESO residencia, a Bond-style lair that actually featured in Bond movie Quantum of Solace.

But the other mountains around were all tested for their clarity of air and smoothness of airflow, and failed to make the grade. Cerro Armazones, a lone curve of a hill with mostly flat desert just around it, was the only one that had the right conditions for this spectacular project.

The next step is all about logistics. The site has clean and pure air because it’s in the middle of nowhere, several kilometres past the signpost to back of beyond. So the ESO team have commissioned construction workers to begin making a new road through the Mars-like landscape up to the mountain.

When we went there this week – filming a piece to feature in Euronews’ Space series in July – the only access to the summit of Cerro Armazones was up a steep path that only a differential-locked 4×4 with off-road tyres and low-ratio gearbox could manage. It’s fun, but it’s no use for building telescopes. So once the main highway to the foot of the mountain is built, the team will then hack out a gentle spiral around the hill all the way to the top.

It’s not just road access that’s a problem. The people building this new telescope will have to live and work here for week-long periods, and they’ll need food, water and somewhere to sleep. Luckily for ESO they’ve done this kind of thing before at several other sites in the Atacama, and this is a part of Chile full of mining and construction contractors used to handling big projects in tough conditions. So between the observatory engineers and the men in hard hats there’s plenty of local know-how on building a new town from scratch in the dust of the desert.

While the foundations are laid, the work on developing the telescope itself goes on in parallel. With the World Cup going on, many of the comparisons being made about the scale of the E-ELT were related to football. So here’s the Top Trumps of the E-ELT: It will be over 80 metres high, as big as a major football stadium, and the telescope’s main ‘eye’ will be almost half the length of a soccer pitch in diameter. For those not familiar with the beautiful game, that means about 39 metres. So it would take you a while to run across it.

The main mirror will be made of 798 hexagonal segments. These segments have to be recoated, at a rate of one per day, in a continuous process. So each segment will end up being recoated once ever two years. I politely request that I don’t have to do that job.

More Top Trumps: E-ELT will gather 13 times more light than the largest optical telescopes operating today, and it will provide images that are 16 times sharper than those from that great eye in the sky, the Hubble Space Telescope. So it will take some absolutely amazing images, of that we can be sure.

Many great space and science projects love to talk of the spin-offs that their innovative technology will offer to the man in the street. Velcro, the world wide web, that kind of thing,. ESO say the E-ELT will have plenty of technology transfers too, and when you consider the cleverness of their adaptive optics system that cancels out interference from the Earth’s atmosphere, then you have to accept that there probably is a use for that kind of tech elsewhere.

But really, this project is about the kind of ambition to make the human race a better and brighter bunch that you find in the finest, most extreme science experiments. Think of the Large Hadron Collider’s quest to understand why things have mass, ITER’s experiment to develop clean and sustainable nuclear energy, or the Planck telescope’s search for the origins of the universe.

The E-ELT is in the elite club of mega-science projects, and when it actually starts to take data and create results, it might just help us to answer one of the biggest questions of them all – are we alone, or are there millions of other life-bearing planets out there just waiting to be visited.