Why Europe needs a chief scientific advisor

November 18, 2014

Further protests over appointment of far-right European culture commissioner

November 20, 2014There is a memorable moment in the film Casablanca in which the unspeakable Claude Rains indignantly exclaims “There’s gambling here!” before the croupier approaches him and says: “Your winnings, sir.” In a parody of that scene, the president of the European Commission, the Luxembourgian Jean-Claude Juncker, appeared shocked by this week’s revelations suggesting 340 multinationals used Luxembourg for tax evasion, and simultaneously promises he will be putting in place measures to avoid this happening again.

Juncker appeared shocked by this week’s revelations suggesting 340 multinationals used Luxembourg for tax evasion.

These revelations, termed ‘LuxLeaks’, which we owe to the work of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism (ICIG), merely confirm what we already knew. In fact, the European Commission itself has been investigating this issue in Luxembourg and other EU members (mostly Ireland and the Netherlands) for years. At a recent press conference, Juncker denied any complicity in these agreements but admitted his political responsibility for what he described as “excessive tax engineering“.

That Juncker – who presided over the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg for no less than 18 years, working also in the capacity of Finance Minister – wants us to believe that he knew nothing creates a rather difficult dilemma. Either he is not telling the whole truth, which should prompt the Parliament to open an investigation, or he is telling the truth but will then have to publically admit such high levels of negligence in the performance of his duties that the credibility he entertained as chair of the Commission would be seriously damaged.

Juncker denied any complicity in these agreements but admitted his political responsibility for what he described as “excessive tax engineering”.

Because the issue here is not that the aforementioned companies took advantage of an obscure loophole to escape their tax obligations and cheat the Luxembourgian fiscal system, but rather that the country’s Treasury signed an agreement with each and every one of them that validated tax schemes allowing them to contribute nothing more than a ridiculous 2 percent. Ergo, instead of cheating the Treasury with some element of uncertainty, these companies cheated their European partners with the full cooperation of Luxembourg’s Tax Authorities, in writing and with his signature at the bottom of the last page.

Luxembourg’s version of events is that all the responsibility lies with the head of the “Society 6” department of the Treasury, which specialises in complex investment vehicles. At Society 6, a now-retired official by the name of Marius Kohl negotiated agreements with the major auditors, including PriceWaterhouseCoopers, on behalf of multinationals and, apparently, enjoyed wide discretion and was not accountable to anyone.

That this functionary was unaccountable, however, is not a valid explanation. But if it was his mission to attract multinationals so that those corporations paid Luxembourg taxes as opposed to ones to other countries, then accountability was met by the mere fact of him attracting money: accruing more than 1.2 billion euros in taxes to distribute among 500,000 Luxembourgian people. This is perhaps why his nickname amongst auditors came to be “Monsieur Ruling”, stemming from his unilateral ability to decide the tax laws that were applied to these big corporations.

Fortunately, there are archives. The Wall Street Journal was the first to visit them and discover an appearance by Juncker in the Luxembourg parliament in which he proudly announced that thanks to his role as mediator, two large companies, America Online (AOL) and Amazon (precisely the company that the European Commission was investigating), moved their offices to Luxembourg (see Juncker’s Past Speeches Hint at Tax-Advocate for Luxembourg).

Instead of cheating the Treasury with some element of uncertainty, these companies cheated their European partners with the full cooperation of Luxembourg’s Tax Authorities.

The seriousness of the issue and its political consequences cannot be underestimated. First, it reveals that the political success enjoyed by Juncker, who allowed these Luxembourgian groups to enjoy an unparalleled standard of living and social security benefits, was built on the back of a fiscal system that, though deemed legal from a formal perspective, was clearly fraudulent in its intent. The Luxembourgian authorities must have had something of a guilty conscience when they rejected requests for information on these practices as overseen by Commissioner Joaquin Almunia at the time, and they must have something of a guilty conscience now, in claiming they will not do it again now that all has been discovered.

But the damage to Juncker’s legitimacy to head the Commission is beyond the scope of Luxembourg. Bear in mind that as president of Eurogroup during the height of the euro crisis, Juncker was at the forefront of policies of austerity and fiscal stability that generated brutal cuts to the quality of living and rights of millions of Europeans. Now it emerges that while this was taking place, today’s president of the European Commission led a country in which he emptied the coffers of his associates just when those taxes were needed most.

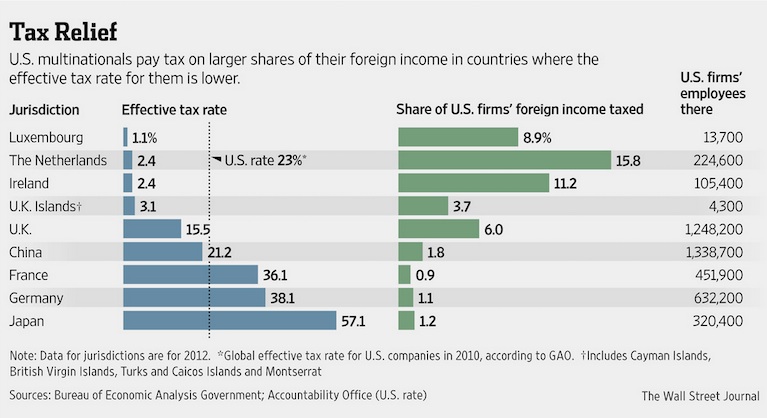

Yet it is not only Juncker who appears in a bad light following LuxLeaks, but rather Europe in general: it demonstrates everything that is wrong with Europe today. While states and citizens are tax supervised to the maximum, with strict spending rules enforced by treaties, multinational corporations roam freely throughout Europe seeking agreements favourable to their interests. Ireland and the Netherlands, see this chart (courtesy of The Wall Street Journal), engage in the very same practices.

Yet it is not only Juncker who appears in a bad light following LuxLeaks, but rather Europe in general: it demonstrates everything that is wrong with Europe today.

Juncker claims this serves as a stimulus to achieve the harmonisation of taxation in Europe, but it is difficult to believe him: it will be a long process, there will be Member States that oppose it, and finally, when it all comes to nothing, Juncker will say: “I tried!” Meanwhile, the citizenry will come to understand Europe as a gambling hall where the games are played with taxes.

Read more on: Reinvention of Europe