Bacca and Sevilla out to create history

October 5, 2014

Supreme Court’s Robust New Session Could Define Legacy of Chief Justice

October 6, 2014The fertility rate in different countries is one of those topics that you might find kind of interesting only in passing. “Oh weird,” you might mutter to your spouse while reading the news, “People in France have more kids than the rest of Europe,” and then you never think about it again.

Maybe you should.

Thinking about it economically, having a lot of people of a certain age could make a big difference to a country. Consider the demand for particular goods and services, or the relevance of certain social welfare programs. A low birth rate means an aging population, and over time that’s necessarily going to impact the fabric of a society.

As it turns out, a country’s age is also a very good predictor of its entrepreneurial activity, which, in itself, is also inextricably linked to economic growth.

Age and innovation

“In the near future,” say the authors of a National Bureau of Economic Research study on the subject, “An aging and shrinking workforce likely will be the norm for most of the world.”

While the U.S. has a “replacement” level of fertility, Europe doesn’t (it’s population is expected to shrink about 20% each generation), and neither does Japan (40% shrinkage per generation) or China.

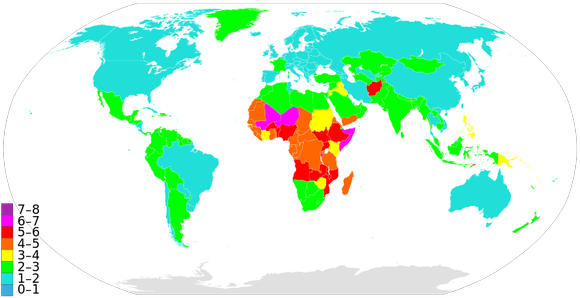

Take a look at this map. It doesn’t have the granularity of the data above, but it gives you a rough idea of how few children are being born per woman in most of the world.

Source: Wikipedia

What effect will this have on business in the future?

James Liang, Hui Wang, and Edward P. Lzear sought to find out. The researchers theorized that an aging workforce would reduce two factors critical for the success of entrepreneurs: the first is creativity (which they assume to be most associated with youth) and the second is appropriately high-level work experience. Fewer young people means less creativity, and with more older people competing for high level positions, there’s less opportunity for a gifted young person to take on a lot of responsibility.

The evidence bears this idea out. Based on their analysis of a global database of entrepreneurial activity, the authors find that for every one standard deviation* drop in median age in a country, there is a 2.5% higher rate of entrepreneurship.

That, according to the study authors, is about 40% of the average rate of entrepreneurship — in other words, it’s pretty significant.

For example: The case of Japan

Japan might be an interesting case in point. After growing furiously for a couple of decades, it experienced a crash and 1991 and never really recovered.

One theory is a lack of entrepreneurship. New firm development went from up to 7% in the 1960s to 3% in the 1990s — less than a third of the American rate.

“Five of the top ten high tech companies in the US were founded after 1985, and their founders were also very young when they established these companies, with an average age of only 28. By contrast, in Japan, none of the top ten high tech companies were founded in the last 40 years.”

Spending hasn’t solved the problem — Japan spends 3% of it’s GDP on research and development activities, but it hasn’t budged the rate of new firm growth.

Maybe it’s the low birth rate

The authors find that an older population affects entrepreneurial activity for every age group, meaning that both young and old are less likely to start businesses when the average age is higher. It’s particularly acute for people in their 30s, who you could argue are the best-equipped to start a business: they’re young enough to have creative ideas, and experienced enough to have the broad-based business skills to bring those ideas to life.

What this means for younger countries

While a nation’s demographics aren’t going to tell you the whole story by any means, the implication I draw from this paper is that a young country that’s growing has a better chance of really taking off over the long run than an old country that’s growing.

So, from an investment perspective, you might want to ask yourself: which are the young, high growth, and high potential markets?

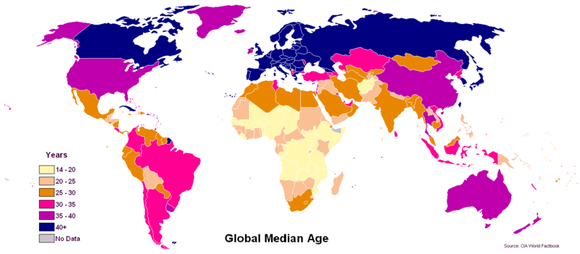

Now take a look at this map from 2005 (it’s a bit outdated, yes, but the changes haven’t been immense).

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The youngest countries are overwhelmingly in Africa, the Middle East, and Southern Asia. Maybe that’s where we should be looking for new opportunities?

Of course, it would be simplistic to say that young people means entrepreneurship means economic growth. You’d think, realistically, that there would be other factors influencing the rate of new business development, and you’d probably be right.

One study found that institutional factors and per capita GDP affect the rate of entrepreneurship. Another also found that entrepreneurship is influenced by the level of per-capita income (alongside “innovative capacity”) and takes a U-shape. That means that the most entrepreneurial activity takes place in both the poorest and richest countries.

How all of these factors interact together to bring economic growth is also not a simple matter. Take Nigeria: it’s average age is 18, and its GDP growth last year was nearly 8%. You might want to sign up based on that alone. But poverty and unemployment are still major problems, and so is government corruption. Hmm.

At the same time, the government is taking pains to boost new and labor-intensive industries. Take it’s import ban on cement, which has resulted in Nigeria becoming a cement manufacturing powerhouse (a good business to be in if you’re in a region with infrastructure and housing shortages).

Are you dizzy yet? Such is analysis.

So you have to strike a balance, and, I’d argue, consider adding demographics into your equation. Age might have some vital role to play in the analysis — either way, it’s something I’ll be keeping in mind.

*Standard deviation measures the “spread” of data around an average. It’s a tool that essentially splits up your “normal” bell curve, where the average is in the middle, into six segments of equal size, with three segments on the left side of the average and three on the right.

So in this case, going by one “segment” from the average age to a younger one gives you a 2.5% rise in the rate of new business formation.