Calls for reform as Italian game reaches crossroads

March 22, 2014

Europe to Launch Hunt for Earth-Like Exoplanets

March 22, 2014 When the Cookbook Store closed earlier this month after thirty-one years in business, it wasn’t just the story of independent bookselling in Toronto that moved one step closer to writing its final chapter. Situated at the northern bookend of one of the last original retail storefront blocks north in Yorkville, the Cookbook Store embodied not just the story of how we’ve cooked and eaten for three decades, but also how an already affluent shopping district evolves without either going up or down the social ladder.

When the Cookbook Store closed earlier this month after thirty-one years in business, it wasn’t just the story of independent bookselling in Toronto that moved one step closer to writing its final chapter. Situated at the northern bookend of one of the last original retail storefront blocks north in Yorkville, the Cookbook Store embodied not just the story of how we’ve cooked and eaten for three decades, but also how an already affluent shopping district evolves without either going up or down the social ladder.

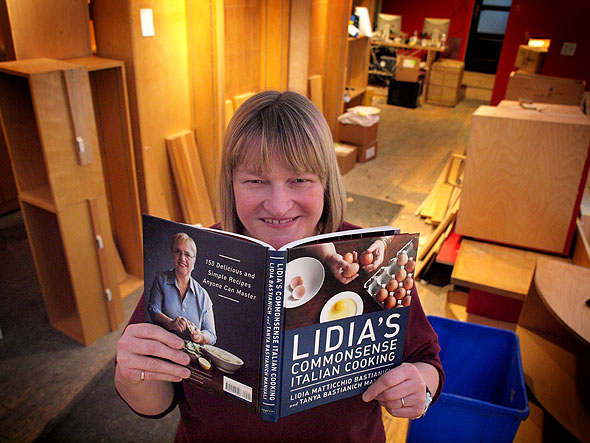

There had already been a cookbook store at the corner of Yonge Street and Yorkville Avenue when store owner Alison Fryer and owner Josh Josephson took over the space in 1983. On a snowy day just after the store’s final day the empty shelves on the wall are the same ones left behind by Books For Cooks – the same ones Fryer had to fill with new stock, after contacting distributors and convincing them that they were going to succeed where the previous store had not.

It was before the internet and even computerized inventory, when rare books had to be ordered by writing a letter to a publisher in Europe, Fryer recalls, and mail orders from customers took weeks, not hours, to fill.

“The only thing I have in common between now and then is that I’d sweep the sidewalk and turn on the lights,” Fryer tells me. “Everything else has changed,”

Across the street, the Central Reference Library was just six years old, and Fryer’s closest bookselling neighbour was Albert Britnell Books, in business for over nine decades by then, and the Cookbook Shop sat at the end of a very bohemian block.

Alongside quirky businesses like Thompson’s homeopathic emporium – on Yonge Street for nearly 120 years in the early ’80s – was just down the row, alongside Av Isaacs’ and Carmen Lamanna’s galleries, which had relocated to Yorkville from the beatnik village on Gerrard, and the Fiesta Restaurant, an old diner recently given a new wave makeover, was a hangout for art collective General Idea.

“When we opened we had a lot of government offices here – don’t forget Workmen’s Comp used to be here,” Fryer remembers. “A lot of head offices used to be here, so a lot of professionals would come in at lunchtime. Now they’ve all moved out, and what replaced them was a lot of residential, so we had the condominiums.”

“The galleries left, the cultural side left, which was sad. I do miss those one-off shops – knitting stores like Calico Cat. Geddy Lee’s wife Nancy Young had (fashion design company) Zapata above us. Fun, artistic, creative people – I miss that. You could walk to eight different bookshops in a couple of blocks.”

In the meantime, the store got to ride the wave of Toronto’s gastronomic revolution – a time when cheques we’d written in the ’70s claiming that the city was shedding its closed on Sundays/steak and baked potato reputation were finally being cashed.

It was a time when houses started getting sold based on their kitchen renovations and not a finished rec room in the basement, and when we suddenly had a generation of our own “celebrity chefs” running kitchens – people like Jamie Kennedy, Greg Couillard, Marc Thuet and Susur Lee.

It was a time when houses started getting sold based on their kitchen renovations and not a finished rec room in the basement, and when we suddenly had a generation of our own “celebrity chefs” running kitchens – people like Jamie Kennedy, Greg Couillard, Marc Thuet and Susur Lee.

Interest in cooking exploded beyond dog-eared copies of The Joy of Cooking or the Betty Crocker cookbook and the tiny group of food freaks who’d read Elizabeth David and watched Julia Child on American television.

“Timing was everything,” Fryer remembers. “We were in the right place at the right time. But we also decided we’d become part of a larger community. A lot of people would come into the store in the ’90s and ask ‘Is this how big it is?’ But you think big, even if you look small. We always wanted to be part of a community and educate people.”

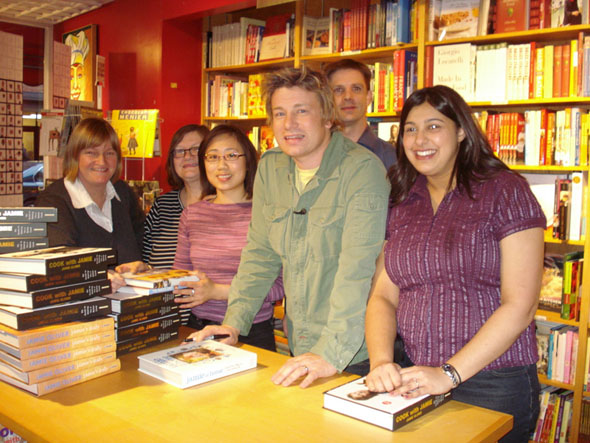

Fryer doesn’t blame new technology or the appearance of 24/7 food television for the changes that would eventually force the store to close. The store’s golden period in the ’90s probably got a boost from the rise of the Food Network, she says, which saw her putting on major events when TV chefs like Jamie Oliver, Nigella Lawson and Anthony Bourdain would come through town.

Fryer doesn’t blame new technology or the appearance of 24/7 food television for the changes that would eventually force the store to close. The store’s golden period in the ’90s probably got a boost from the rise of the Food Network, she says, which saw her putting on major events when TV chefs like Jamie Oliver, Nigella Lawson and Anthony Bourdain would come through town.

It was at one of their first signings, with Emeril Lagasse at the then-new Loblaws on Queen’s Quay, that Fryer knew something big was happening. “We had a lineup of about 1500 people. He signed for six hours – it was insane. And it was completely different demographics – young, old, stay at home, career people. It was incredible. That really showed me the diversity, and they weren’t reading Gourmet magazine – they were watching the Food Network.”

On the day I visit, the shelves are empty and the rows of dusty wine bottles that lined them – souvenirs of memorable meals by staff and patrons – are boxed up, ready to be shipped to George Brown’s culinary school. The building – most of the block, in fact – is due to become part of One Yorkville, a condo complex that’s supposed to preserve the vintage storefronts facing Yonge. Fryer has given her folder of old photos of the building, a gift from the family of a long-gone tenant, to the restoration architects working on the project.

The store will go out with one last hurrah – a pot-luck dinner for staff and patrons tomorrow (Mar. 23) in the empty store. Fryer says that they knew that the condos were coming, but that it was really the juggernaut of online book retailing that’s writing the final page for specialty bookstores like the Cookbook Shop, which is going away to join niche stores like Longhouse Books and Edward’s Books Art in the city’s retail history.

“We’re at Yonge and Bloor – this is where density should be. People ask ‘Are you mad at the condo developers?’ I’m not mad at all. I’m not bitter. We’ve had 31 years. If someone said, Alison, you’re going to start this project which is kind of crazy if you think about it, and you’re going to do this for the next 31 years. Here’s the people you’re going to meet, here’s where you’re going to eat – all those things. I would have said sign me up. We got to live our dreams for the last three decades.”