Don’t blame Justice Ginsburg

July 5, 2014

Think local to succeed in Asia

July 6, 2014

Marco Kerkmeester will never forget the week he opened his first cafe in Sao Paulo. He finished telling his story to three well-heeled female customers, then heard them laughing as he walked away. “My waiter overheard them saying, ‘Imagine a New Zealander thinking he could sell coffee to Brazilians’,” says Kerkmeester. “But they all bought coffee.”

It sounds like the old “coals to Newcastle” joke, but the former Aucklander has pulled it off. From small beginnings he now has seven Santo Grao (holy grail) cafes in Brazil’s largest city and has extended beyond Sao Paulo, opening a branch in Curitiba, 300km from Sao Paulo. He employs more than 200 staff and his turnover is in the millions. “It’s been a great adventure and a hell of a lot of fun,” says the 48-year-old.

Kerkmeester came to Brazil in 2001 with his future wife Renata after they met across the aisle of a plane. After a few months, on a trip back to New Zealand to “pack up his life”, he realised he was looking forward to a decent cup of coffee. “I remember thinking, this is nuts – there must be a business opportunity here.”

Brazil produces more than one third of the world’s total crop (almost six times that of Colombia) but most of the best beans go overseas.

“You were drinking what tasted like charcoal and water just to get your caffeine hit,” says Kerkmeester. “You needed three or four teaspoons of sugar to make it drinkable.”

Coffee was pretty basic and was often served free in restaurants. Kerkmeester wanted to change that. He sourced superior beans from around Brazil, aiming to make the best coffee in the country.

His business kicked off at the same time a gourmet coffee wave swept Sao Paulo, partly fuelled by the burgeoning middle class. Having business meetings over coffee became de rigeur.

Brazil produces more than one third of the world’s total crop (almost six times that of Colombia) but most of the best beans go overseas. Photo / Getty Images

Kerkmeester had to learn some local lessons along the way. Initially, he was open for standard New Zealand cafe hours until a friend told him he was “crazy” to close in the late afternoon.

Now, most of his cafes are open until 1am, and he earns almost half of his revenue after 6pm.

Kerkmeester is also proud of his management philosophies. Every site is 50 per cent owned by one of the staff members. “They don’t just work for me, they work for themselves,” says Kerkmeester.

“The word for boss here is derived from the word patron, or owner, and there is a culture of subservience. We are trying to change those values.”

Kerkmeester has grand plans for up to 40 cafes in Sao Paulo alone, as well as a school for baristas.

He is living the high life, in the city that has the largest helicopter fleet in the world – there are even helicopter taxi services – used by executives to escape the heavily clogged roads.

Kerkmeester describes his typical week as “socially aggressive”, networking and socialising at dinner parties, restaurants and bars, then, like most of the Sao Paulo elite, he unwinds at his beach house.

Sao Paulo has a population of over 11 million. Photo / Getty Images

Liz Gore first came here in 1991 with her then husband, arriving to an economy “out of control” as inflation topped 40 per cent a month. In 1996, she took over the local franchise for an English language academy and now employs 40 staff and looks after more than 1300 students.

“It’s a very complicated country,” says Gore. “A lot of things are great – the climate is wonderful, the people have a contagious passion for life and you can have a very good lifestyle here. But the corruption is hard to live with, as is the lack of infrastructure and security.”

Gore lives in Brasilia, one of the safer cities in Brazil, but her home is still in a compound with electric fences, alarm systems and guard dogs. “Every day is a bearable risk,” says Gore, “and you can’t live life afraid.

“But you need to be careful; if you make a mistake in the wrong circumstances there could be serious consequences.”

She advises visitors to carry “mugging money” rather than running the risk of angering assailants.

“Kiwis can be a bit naive. It’s hard to comprehend the depth of desperation here,” says Gore. “Most of the crime is opportunistic – it’s because of the widescale poverty – but if anything happens, the most important thing is to walk away alive.”

Like many in Brazil, Gore has mixed feelings about the World Cup. “It’s great to bring the tournament here but there has been an insane amount of money spent.

“It doesn’t make sense where you see television reports showing pregnant women lying on sheets on the floor in public hospitals because there aren’t enough beds.”

The Government has spent about 25.8 billion reals ($13.34 billion) on the World Cup and almost a third of that has gone on new or renovated stadiums.

“All this talk about ‘Fifa-standard stadiums’ – locals here just want ‘Fifa-standard’ hospitals, schools and public transport.”

Former Wellingtonian Dylan Hope has spent 11 years in Brazil, mainly working in business intelligence and IT programming. He says there are constant “ups and downs” – he recently spent five hours queuing to change a name for a car registration – but there is plenty to love.

Dylan Hope with his children, Tom and Lui, at the beach in his adopted homeland of Brazil.

“You are swimming all year, the food is wonderful, the tropical fruits are amazing and the people are passionate and enthusiastic,” says Hope. “There is an incredible variety to life.”

It is also different. Even among the middle class, it is normal to have maids and nannies and many live in enclosed communities. For personal safety reasons, after 10pm you don’t have to stop for red lights.

New Zealand sociologist Tom Dwyer, who has clocked up more than three decades in Brazil, says the sheer scale of the country can be difficult to comprehend. It has 36 times the land mass of New Zealand and 50 times the population.

“It’s a young country,” says Dwyer. “There is a lot of energy here, a lot of ambition and drive. And it opens its arms to foreigners.”

A university professor based in the capital, Dwyer has also been a consultant for the Government in high-level trade talks between the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and is president of the Brazilian Sociological society.

“Brazil is a huge economy,” says the New Zealand Ambassador, Jeff McAlister. “It is the second largest emerging economy in the world, behind China, and the seventh largest overall.

“The opportunities are immense.”

McAlister says that over the past decade more than 40 million Brazilians have climbed out of poverty to join the middle class. If the total Brazilian middle class was a country, it would equate to the 12th most-populated in the world, with 100 million.

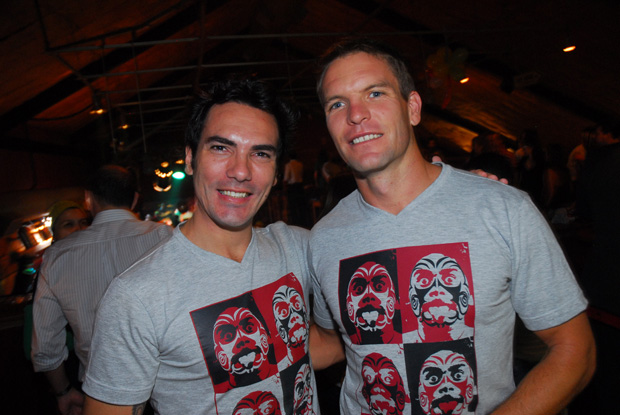

Mark Hindmarsh with business partner Cesar de Raniere, left, at Kia Ora, Hindmarsh’s Kwi-themed bar.

Giving them a taste of Kiwi

Late last year New Zealander Mark Hindmarsh woke up in his Sao Paulo house with a gun pointed at his head.

The 40-year-old former Cantabrian had lived in the sprawling Brazilian city for more than a decade and knew all about the risks of life in the biggest metropolis in the Southern Hemisphere.

Lying in bed next to his Brazilian wife, Vivian, with his three young children sleeping across the hall, he feared the worst. Sao Paulo’s crime statistics make sobering reading, and it is often cited as one of the most dangerous cities in the world.

“It’s a brutal reality of life here,” says Hindmarsh. “My mind was racing but I tried to stay calm – so they would stay calm. I just wanted to do what they wanted and was especially worried about the kids.”

A common tactic here is “Express kidnapping” or “ATM abductions”, where burglary victims are driven around the city to various cash machines, withdrawing the maximum limit at each one, before the person is left on the outskirts of the city to find their way home.

The intruders told Hindmarsh they had eight accomplices downstairs, warning him to co-operate.

Thankfully, they left after a short time, with cash, jewellery and other goods but his family unhurt.

Hindmarsh reflects on the incident as “one of those things” in what has otherwise been a “fantastic” spell in Brazil.

He was immediately entranced by the country while travelling through with a friend in 1999 and decided to stay.

Hindmarsh picked up the language fairly quickly but was unable to land a job in the banking sector, where he had worked in New Zealand and Europe, and realised he would need to start his own business to stay long term.

“I had noticed there were no Irish-style pubs in Sao Paulo,” says Hindmarsh, who was encouraged by his wife’s hospitality background. “I didn’t have any relevant experience, though I had spent a fair bit of time in bars. I thought it could work.”

A typical Brazilian bar is quite different from ours. Most people go to a chopperia, often in a large open area with plastic or wooden tables and chairs. You order from one of an army of waiting staff and your chopp (beer), always well chilled, is delivered in small glasses.

“I’d been to plenty of these places and noticed there wasn’t much interaction between the tables,” remembers Hindmarsh.

“It didn’t feel like a typical pub. Maybe it was personal frustration – here I was, this gringo, eager to try out my Portuguese with the local girls and it didn’t seem possible. I thought I could create a different environment.”

Armed with a capital injection from friends and family, Hindmarsh found a suitable site. But the next steps were complicated.

For a country where life is relaxed and the most common response to questions is “tudo bem” (all good’), Brazil is drowning in red tape.

“In New Zealand, you can open a company in an hour on the internet,” says Hindmarsh. “In Brazil, it can take months.”

Hindmarsh describes huge state “bureaucracy factories”, where all contracts, documents and licences need to be sighted, signed and approved, laughing that it took three months before his company’s printer was officially registered.

The All Black Bar and Grill poured its first pint in December 2001. It was officially opened by Helen Clark during the former Prime Minister’s visit to Brazil to inaugurate the New Zealand Embassy in Brasilia.

“It was a new concept here and Brazilians seemed to like it,” says Hindmarsh.

“Perhaps it was the novelty; sitting or standing at high tables, ordering a drink from the barman, the chance of starting a conversation at the bar or bumping into someone.”

By April 2003 Hindmarsh had opened a second establishment – Kia Ora Bar and Grill, a larger venue that accommodates up to 500 people.

He doesn’t import beer from New Zealand because “it could sit at the port here for three months”. He relies instead on Guinness, but does have some touches of home. The menu includes steak and cheese pies, shepherd’s pie, a kiwi burger and “mouse traps” (vegemite on toast with melted cheese).

“Every night here can be amusing, funny, entertaining,” says Hindmarsh. “When people are happy here you can’t compare it to anything else in the world.”

Hindmarsh, who now runs four bars, has his fingers crossed for Brazil’s football team and says the country will be crushed if it doesn’t prevail in the final next Monday.

“It means everything to a lot of people,” he says.