In scale and ambition, Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life is the Noah’s Ark of visual feasts.The free-to-public show is a multi-narrative epic narrated by 800 photographs and 27 video films. It represents the work of more than 70 South African photographers and comes with a doorstopper of a catalogue – more than 500 pages, weighing 3.1kg.

Because it is conceptually an archival project, fashioned out of existing and often published work and elevated to worldwide collector level by the International Centre for Photography, the work also opens up fascinating and emotional avenues for both the viewer and the artists.

It offers an indirect dialogue between the works of the late photo-graphers, the current seasoned pros and the younger generation.

The show also casts the gates wide open to all sorts of things, because 2014 is a new and different year compared with, say, 1988 – when Sharpeville, Boipatong, Thokoza and Winterveldt were on fire. But also because some of the contributors have either relocated overseas, retired or work in media at variance with the tradition of photojournalism.

It frees up space between practitioners, art institutions, society, critics and curators to engage on a broad variety of matters, such as style, technological trends, ideology, subject matter, experience and the ultimate and inevitable question about commercialism, not only as opposed to art but as art, and vice versa, in the world of visual arts.

You are bound to find, within this heady mix of image-makers, now iconic (then persecuted) names such as Ernest Cole, whose hyperreal documentary book House of Bondage must have been the spiritual muse behind this show, Eli Weinberg, Bob Gosani, Jürgen Schadeberg, Peter Magubane, Ranjith Kelly, Santu Mofokeng as well as an array of those from the “new power” generation led by the likes of Juda Ngwenya, the Bang Bang Club, Fanie Jason and Themba Radebe.

But wait. Where are the women? On a mattress on a bedroom floor grieving for their husbands and sons, as in Miriam Makeba’s aching lyric in the song Hauteng (A Promise, 1975): “Banna ba rona ba shwetse komponeng” (Our men died down in the mines)

The exhibition covers more than half a century of visual production that forms part of what the curators Okwui Enwezor and Rory Bester exhort us perhaps to appreciate, critique and internalise as the “South African identity”.

About that self-assuredness?

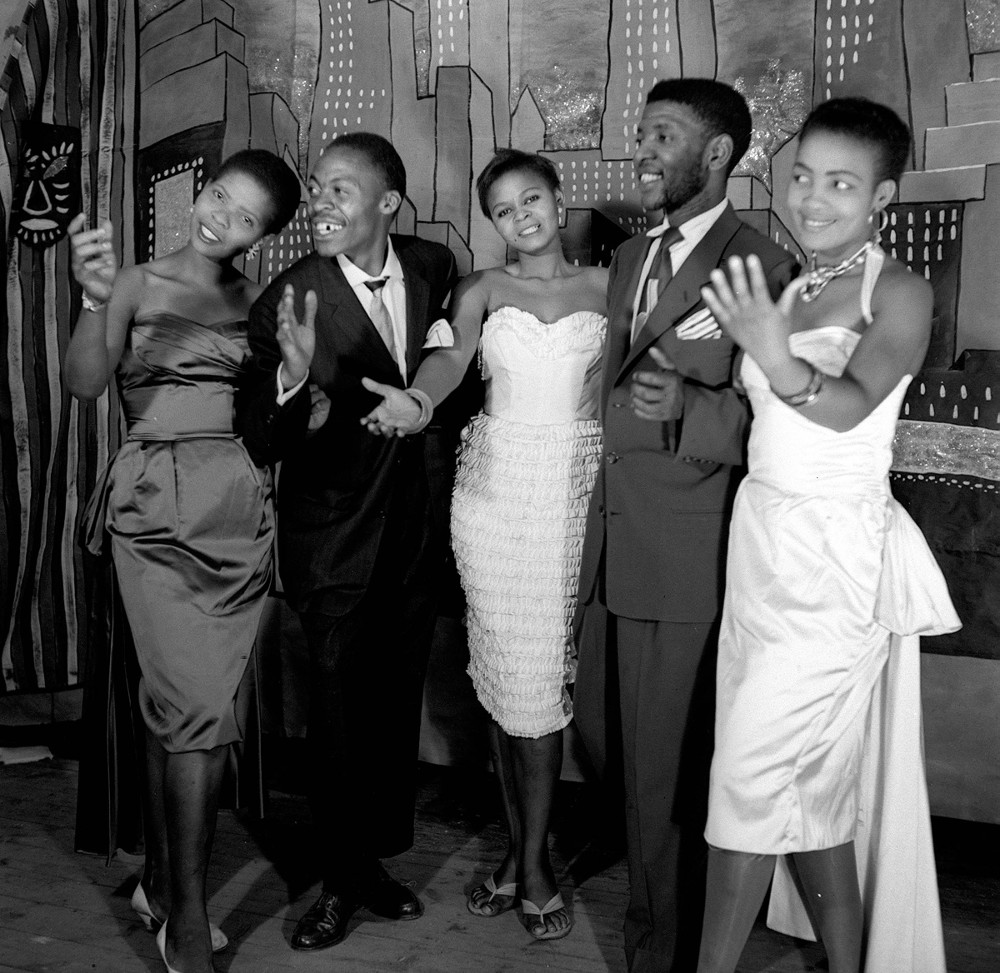

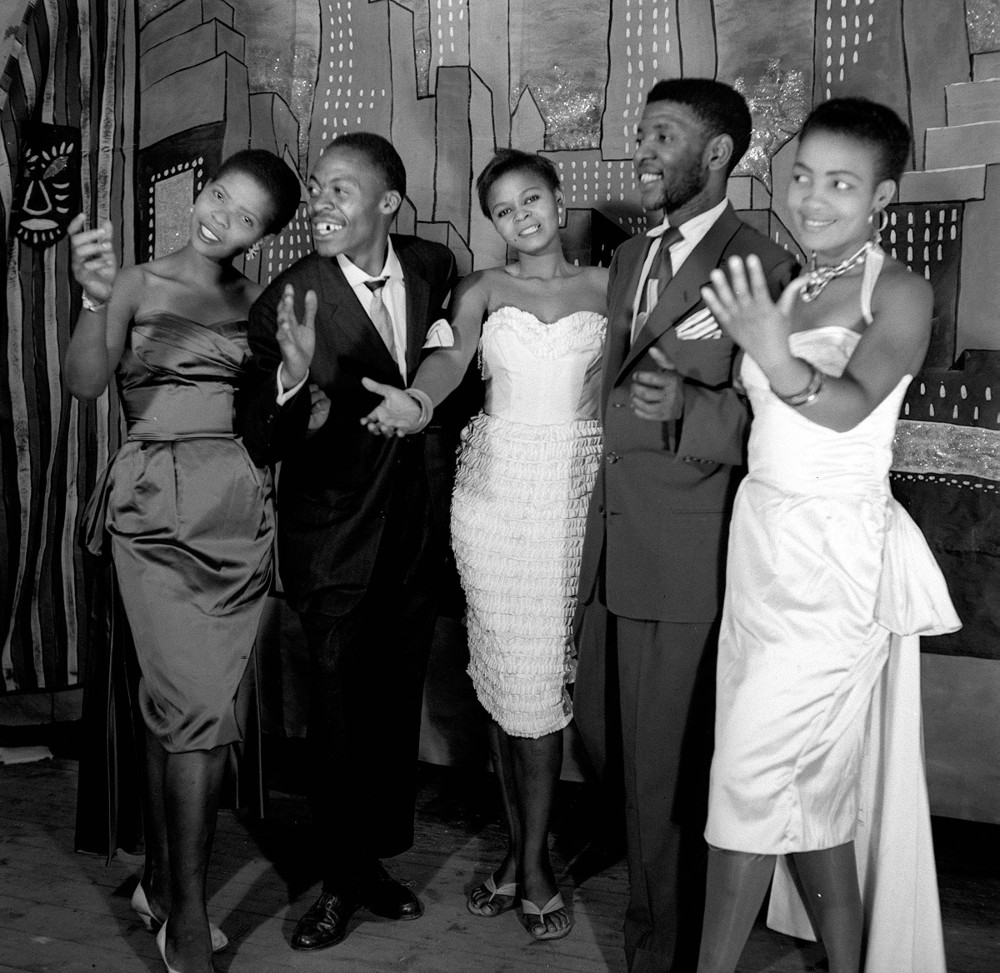

The cast of the show Call Me Mister. Photograph from Baileys Archive

The cast of the show Call Me Mister. Photograph from Baileys Archive

White power threatened by ‘swart gevaar’

Rise and Fall concerns itself with everyday South African life and power relations since 1948, which calls to mind the words of Hannah Arendt. In a chapter entitled Race and Bureaucracy, from her seminal text The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt writes with an almost uncharacteristic tongue in cheek about the year 1948.

I reserve the pleasure of paraphrasing her in her take on racism in South Africa: Racism is the lousy project initiated by a bunch of losers from Europe. English outcasts and thugs, European hustlers and adventure-seeking weirdos arrived midway to India to find Dutchmen trying to deal with how the bloody hell the European should survive in this unforgiving topography.

On closer reading, she implies that the 1948 National Party victory amounted to nothing more than a Mafia pact between those earlier descendents to now rule the native, whom she annoyingly keeps on referring to as the “savage” with no discernible sense of irony.

This painstakingly researched visual epic commences right at that moment when White Power agreed to eliminate what in their lopsided view was the looming swart gevaar.

An exhibition with stark imagery

What impresses is that the exhibition is vast. But that is an artistic challenge, not manna from heaven. Abundance of material does not mean the messaging, aesthetics and creative direction will be any easier. In fact, too much is often a recipe for disaster.

But the curators pull if off. They attempted to countenance the archetypical struggle image: the bloodied frame riddled with bullets, darkened by smoke, coarsened by rage – your rage, the viewer – and overtraumatised by a pack of police hounds mauling “the savage”.

As with the image of police brutality in the Jim Crow and civil rights-era United States, the bloodied and the hound-savaged image is indeed our story. A wounded part of it at that – there’s no way of getting around it.

Cue Lady Day’s Strange Fruit: “Southern trees bear a strange fruit/ Blood on the leaves/ And blood at the root/ Black bodies swingin’ in the Southern breeze/ Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees.”

But is that our only story? Black folks’ struggle imagery can’t be reduced to stories of humiliation, of shredded clothes and public signs disqualifying Africans from enjoying such natural wonders as the beach. Such wounded simplicity just won’t do. Not for long, anyhow.

Enwezor and Bester managed to source some images showing folks in discernible settings just like any other people – having fun, clad in church uniform, hanging out in public spaces and, yes, jiving the bejesus out of their oppression, if only momentarily.

“You talk about elegance, dignity and sartorial style of Africans under apartheid,” says Enwezor. “Perhaps. But let me tell you now, it is not possible, now or whenever, to look at apartheid and find anything to celebrate about life under its monstrous claws; that period. But if there’s anything to celebrate, it’s the work of South African photographers. The skill and the heart with which they narrated life shaped by that.”

Still there are also eye-popping images celebrating that aesthetic and revolutionary expression not given its proper due in struggle literature, textual and visual – style. Much as I commend them for looking wide into their viewfinder for visual testaments beyond photographing the blues of the land, I also believe some of the photo selection could have benefited from depth and specificity, such as beauty during apartheid, sport as defiance under apartheid, exterior architecture and interior décor under the ugly surface of apartheid, and so on.

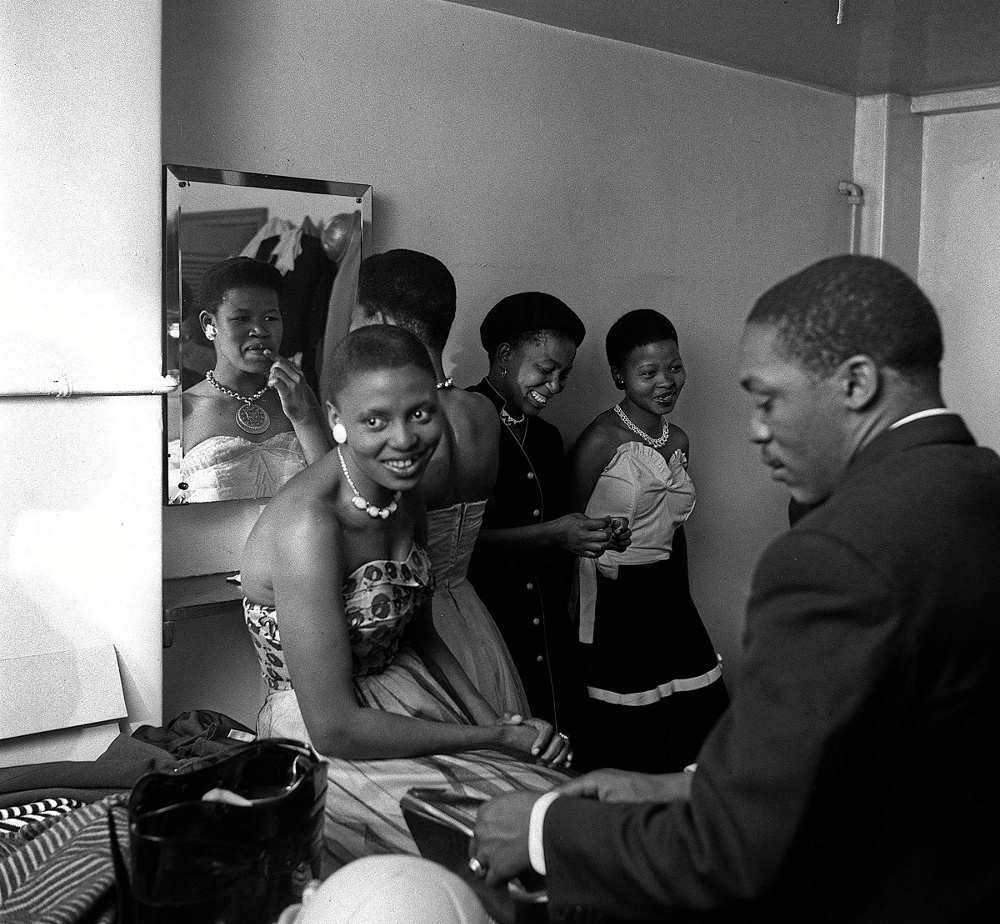

Photography from Bailey’s Archives

Here, the Bailey Archives, from which the glorious pictorial magazine Drum of the 1950s comes, serve as the reservoir for a variety of lifestyles. Out of the essays included, there is not a single one that cogently puts an argument for various lifestyles such as sports.

Miriam Makeba at Shantytown in City Hall . Photograph by Bob Gosani

Miriam Makeba at Shantytown in City Hall . Photograph by Bob Gosani

Dramatisations of street sass – notions of sexiness and naughtiness – are also rather skimpy.

Where are those achingly beautiful sexy photos Alf Kumalo shot and used in his book Through the Lens? The cover shot of two women clad in extremely beguiling fashion, one with a Saartjie Baartmanesque nyash and the other with a less daunting behind and a killer pair of legs in black stockings, performing a sort of erotic bump-jive-jazz routine, is an image and experience literally to die for.

Where is that sort of radical lightness and the deeper intellectual argument about what constitutes pleasure, play, culture and/or joy? It is at times like this that I begin to miss those self-absorbed butch feminist and queer discourses on politics and the booty.

But, hey, don’t despair; there are some nuggets here showcasing black folks in their various interpretations of sartorial elegance. Check Weinberg’s 1982 photo of a dapper old man with an ageless, outward strut, spruced up in a loose-style dark suit and fedora, carrying a suitcase. He is the picture of dignity.

Of course, we should touch on the obvious and well-known photos of the black stars and members of the African intelligentsia and performers, and move on hurriedly, as there is so much to linger on, to photos of ordinary black folks who laughed, shone and exuded oceans of swagger.

Oh, heita daar, Nelson, cat, who’s your tailor? There’s that Schadeberg photo of Nelson Mandela in a double-breasted suit and a hanky, matching tie, hair parted just at the right angle, walking through the bustling crowd with a heavyset man in a three-piece, fedora and spit-licked black brogues.

The lens tell a different story

It’s during a break at the 1958 Treason Trial in Pretoria and either man could be sentenced to life imprisonment or be mauled by a police dog right there, but the expressions on their faces – the statuesque Mandela gaily laughing, his buddy about to a light a fag and inhale – just said they couldn’t give a toss. Point blank, it’s a lady-killer image.

There’s also that iconic GR Naidoo photo, captioned Dig This Musical. It’s either a publicity still or a piece of front-row art reportage from an Alan Paton-scripted and Todd Matshikiza-scored musical revue, Mkhumbane. The actor, a male figure in a cream-white zoot suit and a square-shaped-top fedora dances up a storm with a young woman in a print maxi dress, each seeming to pull the other in their opposite ways.

It evokes special memories of a similarly themed Malick Sidibe photo of a young, sweaty couple getting down to what I can only imagine to be Cuban rumba music in Bamako, circa late 1960s. The image has gone viral and several so-called world music compilation tapes use it for a sleeve image either inside or as a cover. Like that image, Naidoo’s Mkhumbane photo is racy and riotous. Dig that!

Several images expand, mimic, act out, internalise and dramatise this sexy-elegance and dignified-defiance aesthetic, such as the photo by the less well known Jerry Ntsipe.

Did I ever tell you about the young racially indeterminate dame, Selina Koloe, in a picture shot by Ntsipe? Selina could have passed for anything she desired: African, European, Griqua, Indian or Malagasy Creole, and you would have been none the wiser. She’s gazing at herself in a hand-held mirror, her hair flowing back into the shade of her umbrella on what looks like a beach (although photographers and their subjects were equally adept at make-believe beaches and other prop settings), with a leather handbag that could have been from Macy’s or Micciua Prada next to her.

And then there are two photos of classy sisters, either going to or coming from a day’s hard toil at the madams’ ‘burbs on foot. It is during the infamous 1957 Alexandra bus boycott.

They wear an air of confidence. It must have been summer or spring. They are clad in short sleeve and sleeveless tops, with figure belts, nipping and tucking them in the right places. It is in the middle of one of the fiercest and most radical defiance campaigns since the dawn of apartheid and yet all these women in Weinberg’s photos are the embodiment of what their grandchildren today refer to as “awesomeness”.

These photos remind me of what I have been missing in contemporary representations of black folks: beauty and style as the language of pleasure and defiance.

They also remind me that, for years, I have been half-depressed because of the cherished tropes of 20th-century popular black life: sex, booze, self-mutilation, violence, cars, God and voodoo, in that order.

A few years ago I was privileged to see a travelling show about the bad-ass jazz rebel and ultimate aesthete Miles Davis, with a title pilfered from one of his 1980s comeback works, We Want Miles.

Looking at Enwezor’s tour de force of a sizeable chunk, if not the most important chunk, of our recent past, all I can say is, we want more of those fly blacks.

Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, an International Centre for Photography show, opens at Museum Africa on February 12 l For more of the images see our slideshow at mg.co.za/riseandfall