RECEP TAYYIP ERDOGAN has reason to thank Vladimir Putin. For weeks the Russian president’s attack on Ukraine has hogged headlines. This has let Turkey’s prime minister get away with only limited international opprobrium for a string of illiberal laws that seem designed mainly to protect himself and his allies from a corruption scandal that one insider calls the biggest in modern Turkish history.

Since the scandal broke in mid-December, when police raided the homes of several sons of ministers, illicit recordings have emerged on the internet supposedly implicating Mr Erdogan, his relatives and others in dodgy dealings. Mr Erdogan has denounced these as fabrications, and blamed a network of judges, prosecutors and police linked to Fethullah Gulen, a powerful Sunni Muslim cleric based in Pennsylvania. (The irony that Mr Gulen was an ally of Mr Erdogan in his previous legal battles against the army and the secularists has not escaped Turks.)

Mr Erdogan has reassigned or sacked hundreds of policemen, judges and prosecutors, stalling the investigation. He has passed laws giving the government greater control over the judiciary and security services, clamped down on the media and tightened internet regulation. His latest move was to get the internet regulator, a former spook, briefly to ban Twitter, and he has often threatened other social media as well (see article).

Mounting criticism of the prime minister has left him unmoved, just as it did after he unleashed a brutal police assault on protesters in Istanbul’s Gezi Park last summer. Besides attacking Gulenists and protesters, he has responded with digs at the foreign media and a purported “interest-rate lobby” (in January the central bank doubled its rates to 10%). And he defiantly declared that the Twitter ban showed to the world the strength of the republic.

Above all, Mr Erdogan relies on one overarching claim: that he has the support of voters. Ever since his Justice and Development (AK) party was catapulted to power in November 2002, its electoral success has been impressive. AK’s share of the vote rose to 47% in 2007 and almost 50% in 2011 (though it fell below 40% in municipal elections in 2009). Mr Erdogan has adopted a fiercely majoritarian attitude: so long as voters back him, he is entitled to do whatever he wants, heedless of opponents, protesters, judges, prosecutors or Europe. In a country with weak institutions and few checks and balances, such a view inevitably tends to authoritarianism.

On March 30th the prime minister’s support among Turkish voters will be put to the test, for the first time since the Gezi protests and the corruption probe, in municipal elections. Mr Erdogan has explicitly turned these into a referendum on himself and his party. If AK does well, which most analysts reckon means winning over 40% of the vote and keeping control of both Ankara and Istanbul, Mr Erdogan will claim vindication for his tough policies.

The outcome is highly uncertain. The main opposition parties, the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) are weak. AK remains very strong in its Anatolian heartland, which includes such cities as Bursa, Kayseri and Konya. But Mr Erdogan’s approval rating has fallen over the past year. The CHP is quietly confident of winning Ankara, and it even hopes to upset AK in Istanbul, the city where Mr Erdogan began his political career. If AK does that badly, one minister predicts, it might even split.

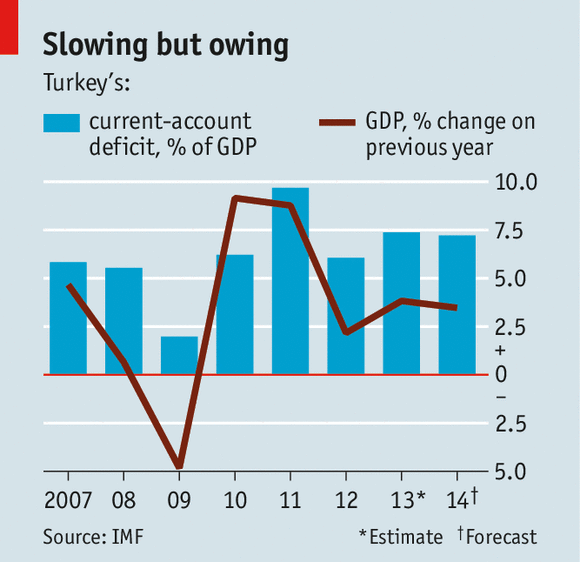

Besides his 11 years in office, Gezi and the corruption cases, another reason why some Turks are tiring of Mr Erdogan is the economy. During AK’s time in power, GDP per head has tripled in real terms. After a sharp drop in 2009, growth bounced back to China-like levels in 2010 and 2011 (see chart). But this year it may be barely above 3%. The IMF reckons trend growth has dropped from 7% to 3%, too low to stop unemployment rising. Turkey also has the biggest current-account deficit in the OECD rich-country club, making it vulnerable to a loss of foreign confidence. Not surprisingly the lira has tumbled, shedding some 24% of its value against the dollar since last April and pushing up inflation.

Mehmet Simsek, the finance minister, rejects warnings about the economy as alarmist. He says all emerging markets have suffered since America signalled that interest rates might start rising. The current account was hit by high gold imports. Worries about corporate exposure to foreign-currency debt are exaggerated: most is owed by the biggest exporters. For the long term, he talks of better infrastructure, education (he points to 400,000 extra teachers and 210,000 extra classrooms) and more investment in RD. He notes that Turkey has climbed from 71st to 44th in the World Economic Forum’s competitiveness table.

Yet Turkey’s weaknesses are obvious. Female participation in the workforce is the lowest in the OECD. Inequality is alarmingly high. Turkey comes a lowly 69th in the World Bank’s “Doing Business” rankings. In many ways it is in a middle-income trap: the low-cost advantage that the Anatolian tigers had in textiles, furniture, white goods and carmaking has been eroded by rising wages (and prices), but productivity and skills are not good enough to switch easily to higher-value production.

Above all is the uncertainty about Turkey’s political direction. Although the new European Union minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, talks of 2014 as the year of the EU, he concedes that popular support for EU membership has fallen from 70% in 2005 to only 40% today. In truth EU membership talks are stalled, and they are unlikely to revive soon, not least because Mr Erdogan has lost interest. He is also said to have become more dismissive of Turkey’s NATO membership. Losing the EU anchor, in particular, worries businessmen. Muharrem Yilmaz, chairman of Tusiad, the industrialists’ lobby, complains that the government did not take advantage of EU membership talks to strengthen political and economic institutions, and that its reform momentum has run out.

What might Mr Erdogan do next? He had hoped to stand for president in August, when the term of the incumbent, Abdullah Gul, a co-founder of AK, runs out. Mr Gul, who has avoided clashing directly with Mr Erdogan but made clear his unhappiness with his restrictive laws, could then become prime minister. But recent events have reduced the chances of Mr Erdogan stepping up to the presidency, not least because he has been unable to amend the constitution to give the job greater powers. So he may prefer to let Mr Gul run again and instead scrap the internal AK party rule against any MP running for a fourth term. That would let him stay on as prime minister and perhaps bring forward the general election due next year.

Yet such a move would only confirm criticism of Mr Erdogan’s autocratic ways. Some even draw analogies with Mr Putin’s desire for a fourth term as Russian president. Aykan Erdemir, a young CHP MP, says the situation makes him think of other embattled leaders in their bunkers, surrounded by yes-men. Put simply, the prime minister lacks an exit strategy. It would be better for his country if he found one.