A scene from the April 8, 2014, brawl in the Ukrainian Parliament. (Vladimir Strumkovsky/AP)

Eggs are thrown and noses bloodied in the Ukrainian parliament. South Korean legislators use fire extinguishers and an ax to break into a barricaded committee chamber. The Venezuelan parliament becomes the site of a raucous fistfight. An antebellum U.S. senator is brutally caned by a member of the House in the Senate chamber. Even typically sleepy school board meetings in East Rampo, New York, collapse into shouting matches between parents and board members.

Why do legislative sessions breakdown into shouting, name calling, and even violence?

We’ve been gathering and analyzing data to answer this question. The locations where brawls occur and the issues legislators fight over vary widely — from the presence of Russian naval bases in Ukraine, South Korean press ownership rules, the amount of speaking time that Venezuelan legislators are given, slavery in the United States, and special education funding in East Rampo, New York. But they all share something in common: what social scientists call a “credible commitment problem.”

A credible commitment problem occurs when conflicting sides are not able to make the other side believe that they will actually stick to an agreement reached through peaceful bargaining. This makes it unlikely that either side will make a peaceful bargain to begin with. Two situations make credible commitment problems particularly bad: when the sides are bargaining over future power and when power is changing because of some outside reason. In these circumstances one or both sides will likely believe they have more to gain from fighting than reaching a peaceful agreements.

Legislative violence is often caused by similar problems, even though legislatures might seem like forums for peaceful problem-solving. For example, if one legislative faction is pushing for laws that will help them win future elections, they won’t want to restrain their power. Moreover, broader changes in society — say, demographic changes — may mean that a party will soon have a dominant majority. This also gives them an incentive to fight rather than bargain.

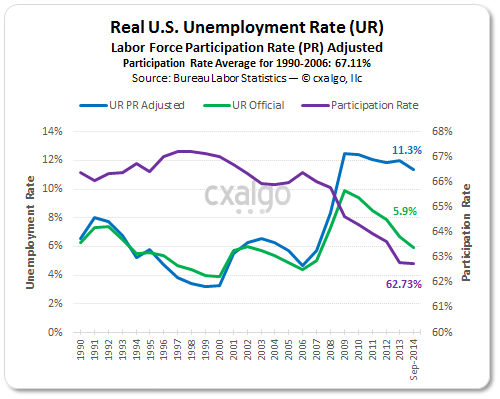

These problems are more likely to occur in two kinds of countries. The first is countries with very disproportionate electoral systems. High disproportionality means that one side could have much more power than they currently do if the electoral laws were changed. This gives them a reason to fight, sometimes literally. The graph below shows how legislative brawls are more likely in disproportionate systems:

Second, brawls in are more likely in newer legislatures—where institutional norms might not have had time to develop, making problems of credible commitment more difficult to address. The graph above shows how older democratic systems are much less likely to experience a legislative brawl.

In Ukraine before the outbreak of the actual civil war, the legislature was plagued by credible commitment problems and thus by violence. These conflicts were about gaining or preventing increases of future power. Ukrainian political parties and the national legislature are largely divided along linguistic and geopolitical lines. Pro-Western parties dominate in the center and west of the country. Pro-Russian parties dominate in the east and south. Each side presses for closer integration with either the European Union or Russia. Closer integration with Europe, pro-Russian Ukrainians believed, would advantage pro-Western politicians in the future. Pro-western politicians similarly fear moves that cement and increase Russia’s presence in the country.

This was the situation in 2010 when a spectacular brawl occurred during the ratification of the treaty to continue leasing port facilities to Russia’s Black Sea fleet. Other brawls have occurred over legislation to allow the use of the Russian language in public institutions, and recently over decisions to send troops to fight separatist groups in eastern parts of the country.

Credible commitment problems are behind brawls in other countries’ legislatures. A South Korean brawl in 2009 was a fight over media ownership rules. Left-leaning opposition politicians worried that allowing increasing conservative media ownership would disadvantage them in future political contests.

Rep. Preston Brooks’ caning of Sen. Charles Sumner in 1856 was predicated on changing demographics in the United States that favored free over slave states. Bolstered by these changes, abolitionists like Sen. Sumner pushed for the end of slavery. Fearing an end to the balance of power between free and slave states, slavery advocates like Brooks had little to lose from using violence in a vain attempt to suppress the emerging legislative majority.

These problems can even be seen at the local level in East Rampo, New York. The town’s Hasidic community is capable of organizing overwhelming electoral majorities. This means that they can shift resources to Hasidic groups, including private special education. Their electoral power makes it almost impossible for them to credibly commit to fully funding the local public schools. This American Life quotes one Hasidic board member as saying:

…we have all the power. Why would we negotiate? If we do, we only have things to lose.’

Because of this, non-Hasidic residents feel that they have no other options than disrupting school board meetings.

Although legislative disruption and brawls may seem like unpredictable, spontaneous outbursts, we think there is a logic underlying them. They are often the result of underlying circumstances that make it difficult for legislators to credibly commit to follow peaceful bargains.

Christopher Gandrud is a post-doctoral researcher at the Hertie School of Governance and Emily Beaulieu is an assistant professor of political scientist at the University of Kentucky.