With the Russian annexation of Crimea already a fait accompli and an invasion of Eastern Ukraine looking ever more likely, it’s sometimes hard to remember how the crisis actually started: with Ukraine’s prospective integration into the European Union. Viktor Yanukovych’s last-minute rejection of an “association agreement” that would broadly liberalize trade with Europe brought hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians out into the streets and rallied thousands of them to the barricades. Ukrainians braved freezing temperatures, police brutality, and even sniper fire. Despite the heavy price they have already paid, a large percentage of the Ukrainian people persist in their quest for a European future. While admirable, Ukrainians’ struggle to be part of Europe poses a simple, yet crucial question—do they know what they are fighting for?

Given Ukraine’s omnipresent corruption, the lack of legal security and, most importantly, the country’s economic implosion, it is not surprising that many citizens would latch onto a symbol (“Europe”) that is associated with all of the things that the country itself lacks. Throughout Ukraine, Europe is popularly identified with economic prosperity, transparency, democracy, and the rule of law, with the possibility of living a “normal life” of dignity and material security. However, what if EU membership is a false promise? What if the stories Ukrainians have heard about economic convergence and prosperity simply aren’t true?

The association agreement was aggressively promoted by EU bureaucrats as the answer to Ukraine’s many economic problems. By bringing its institutions up to par, by lowering barriers to trade, and by adopting European health and safety standards, Ukrainian exporters would swiftly gain access to the world’s largest single consumer market. Given Ukraine’s relatively well-educated workforce and its extremely low labor costs, this would, after a period of adjustment, prompt a boom in light industry and put Ukraine on the path to rapid convergence with Western European living standards. Or so the story went.

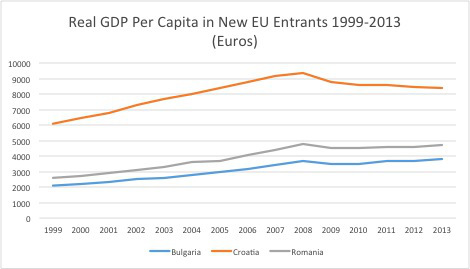

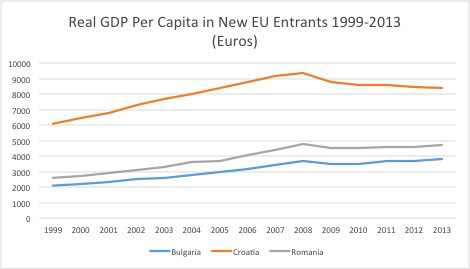

While certain Eastern European countries (particularly Poland and Slovakia) have made impressively rapid economic progress over the past two decades, the reality of “convergence” is substantially more complicated than the simple narrative of “reform leads to growth.” The three most recent entrants to the EU (Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia) have performed terribly since the onset of the financial crisis. Croatia, in particular, has seen no economic growth for the past seven years. After many years of painstaking reform, per capita incomes in these countries are still less than 40% of West European averages. Even more alarmingly, these three countries have almost entirely stopped converging with the “old” EU members in the West. In fact numerous Western countries, such as Germany and the UK, are currently growing more rapidly.

Promoting the EU as a “solution” to Ukraine’s far more serious economic problems is disingenuous and even institutionally corrupt: The track record clearly shows that the EU accession process cannot function as a substitute for effective national-level economic policy making. When national policy-making is well executed, the EU can serve as goal-setting mechanism, as a way for helping people to set ambitious aspirations. But when policy-making is poorly executed, the EU simply cannot pick up the slack: The accession process falls far too heavily on national governments for Brussels to be expected to fix everything.

The other problem to note is that support for economic reform is much weaker in Ukraine than it was in other recent EU entrants. A recent poll conducted by the International Republican Institute shows the Ukraine is characterized by stark regional differences in the willingness of people to suffer through “painful reforms,” and there is no true societal consensus on whether Ukraine should be a part of “Europe,” whether it should be a part of “Eurasia,” or whether it should (as it has for the past 23 years) have one foot in the East and one foot in the West. In Eastern Ukraine, the country’s economic center of gravity, a plurality of respondents still express a desire to join the Russian-led customs union while support for the is EU is as little as 20%.

Given the uncertain economic track record of recent EU entrants and Ukraine’s critical situation, the emphasis from the new government in Kiev should not be on “convergence” or on achieving rapid GDP growth. While a rapidly growing Ukraine would be nice, it simply isn’t going to happen and public assurances that it will happen will only lead to second guessing and recrimination when reality inevitably fails to match the lofty rhetoric. A focus on legal and institutional reform, an effort to make Ukraine’s political system more open, transparent, and democratic, however, can have an immediate impact. Unlike in the economic sphere, there is a genuine consensus in Ukrainian society that corruption should be fought and that citizens should have a more active say in how they are governed.

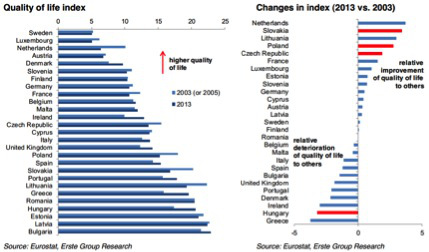

And it is exactly in political reform–reducing corruption, improving rule of law, and building democratic institutions—that the EU has the clearest track record of success. While their economic performance has varied wildly, all countries that went through the EU accession process saw substantial improvements in perceptions of legal security and the rule of law as well as in the strength of their democratic institutions. And although some countries continue to struggle with entrenched corruption, a tangible reduction in levels of corruption has been recorded across all new EU members.

We advocate caution because of the danger of inflating public expectations. Experience throughout Eastern Europe has shown that extremist and populist parties thrive when “responsible” parties make exaggerated promises. Exaggerating the economic benefits of joining the EU could very easily set up Ukraine for even greater political instability and public discontent in the future, something which should be avoided at all costs. Rather than tout economic benefits that are likely to be underwhelming, both Ukrainian and European politicians should highlight the possibilities of political, legal, and institutional reform. This is a sort of “back to basics” approach, in which the EU focuses on what it is best at (building democratic institutions) while shying away from what it is not very good at (forcing countries to reform economically). If the people of Ukraine still desire to join, it will be a story of successful membership rather than one of disappointment fueled by false promise.

We welcome your comments at ideas@qz.com.