EU will shift its focus in Bosnia at economy

February 22, 2014

Neil Lennon: “I Want To Manage Celtic In The Premier League”

February 22, 2014

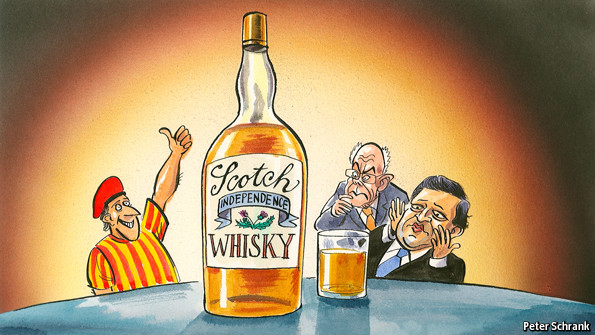

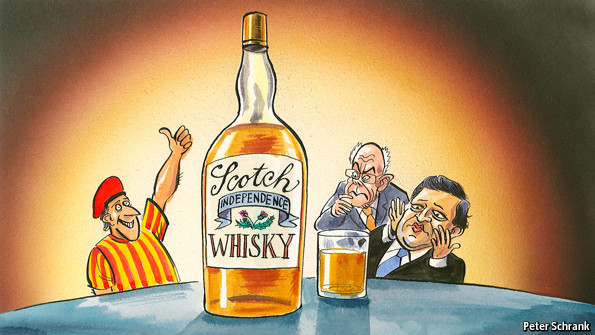

DAVID CAMERON has won few friends with his demands to renegotiate Britain’s relationship with the European Union. But there is one place where he is admired: Catalonia. This is not because he wants a referendum on EU membership, but because he is letting Scotland vote in September on independence from the United Kingdom. The Catalans plan their own ballot two months later, although Spain’s prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, has vowed to stop it. Proof, say Catalan nationalists, of Britain’s deep democracy and Spain’s lingering authoritarianism.

Romantics see parallels in the fate of Scotland and Catalonia, both small nations merged into larger kingdoms in the early 1700s that now seek to rule themselves. Other governments are nervous. If Scotland or Catalonia become independent, why not the Basque Country, Flanders, Corsica, or even Bavaria?

A young man in a hurry

Senior leaders in Brussels have taken to issuing increasingly blunt warnings to would-be breakaways. Speaking in Madrid in December, on the day when Catalonia fixed a date for its referendum, Herman Van Rompuy, president of the European Council, said any secessionist region would be treated as a new country, to which the EU’s treaties would no longer apply. Such a “third country” would have to submit an application to rejoin. That these comments came from a Flemish-speaking former prime minister of Belgium, who said his own deeply divided country should stay together, added weight to his views.

On a visit to London last weekend, José Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission, delivered an even harsher blow. He said it would be “extremely difficult, if not impossible” for Scotland to secure the agreement of the 28 other countries to join the EU. One reason, he added, was opposition from Spain, the most intransigent of the five EU members that still refuse to recognise the independence of Kosovo. Mr Barroso claimed he did not want to interfere in the Scottish debate but that is what he did—and he may have gone too far. As the man who runs the commission, he is entitled to set out his views of European law. But he should not judge the likelihood of a successful application, speak on behalf of Spain, or suggest that peaceful referendums in western Europe are equivalent to the violent break-up of a Balkan country. After all, the commission’s job is to assess accession applications impartially.

Perhaps the anglophile Mr Barroso worries that, if Scotland votes itself out of the United Kingdom, the more Eurosceptic remnant of Britain would be more likely to vote itself out of the EU in 2017. Already struggling to deal with the repercussions of the euro crisis and the rise of anti-EU populists, Brussels would rather not have to contend with secessionists as well. Breakaway regions would add more small countries to an already unwieldy organisation. And fragmentation runs counter to the ethos of uniting to create a greater whole.

Unwittingly, the EU may be part of the problem. It has weakened national governments from above, by shifting powers to the European level (especially in the euro zone). And it has weakened them from below, by making it easier for separatists to seek independence within the cocoon of the EU. Francesc Homs, a senior member of the Catalan government, says the referendum could never happen without the EU, which steadied Spanish democracy after Franco’s dictatorship. “We feel safe and secure. We have lost our fear. Nobody is going to shoot us.”

The treaties allow countries to leave the EU but are silent on what happens if they break up within the club. A split would be unprecedented, even though several EU members were born of earlier secessions. The three Baltic states broke away from the Soviet Union; the Czech Republic and Slovakia came out of the “velvet divorce” of Czechoslovakia; Slovenia and Croatia emerged from the violent implosion of former Yugoslavia. The rest of the western Balkans is also moving closer to the EU. Serbia has begun membership talks, and even Kosovo is negotiating an association agreement, the first step towards membership.

It is wrong, therefore, to insinuate that newly independent states could never join the EU. Would Montenegro and Macedonia really be admitted faster than Scotland and Catalonia, which already apply the EU’s rules? Yet it is still more dishonest to pretend that accession would be quick or easy, even in the best of circumstances. All EU members must agree to open and then conclude membership talks, and to ratify the deal. There are 35 chapters to be negotiated; and these have become harder over the years. Scotland wants to maintain Britain’s opt-outs from the euro and from the Schengen free-travel zone, but opt-outs take longer to approve. Catalonia would somehow try to stay in the euro zone without going through the required qualification period. Would the European Central Bank give its banks liquidity? EU officials reckon it would take at least four to five years to negotiate and ratify the accession of Scotland and Catalonia.

What price freedom?

An amicable break-up, in which all accept and respect the outcome, would surely make for faster Scottish accession. A rump Britain might then be a strong supporter. Spain, despite its qualms, has not said it would stand in Scotland’s way. Its refusal to permit a referendum in Catalonia suggests it realises that, in the end, the EU cannot turn down a breakaway region. But a bitter divorce, with rows over the division of assets and liabilities, would make EU accession harder. Scotland’s path to the EU could then be blocked not by Madrid but by London.

Divorce means breakaways must live as singles, at least for a time. There will be no instant betrothal to the EU, no dowry from Brussels—and no cheques guaranteed by other central banks. Scary or liberating, that is the meaning of independence.