Daniel Pearl

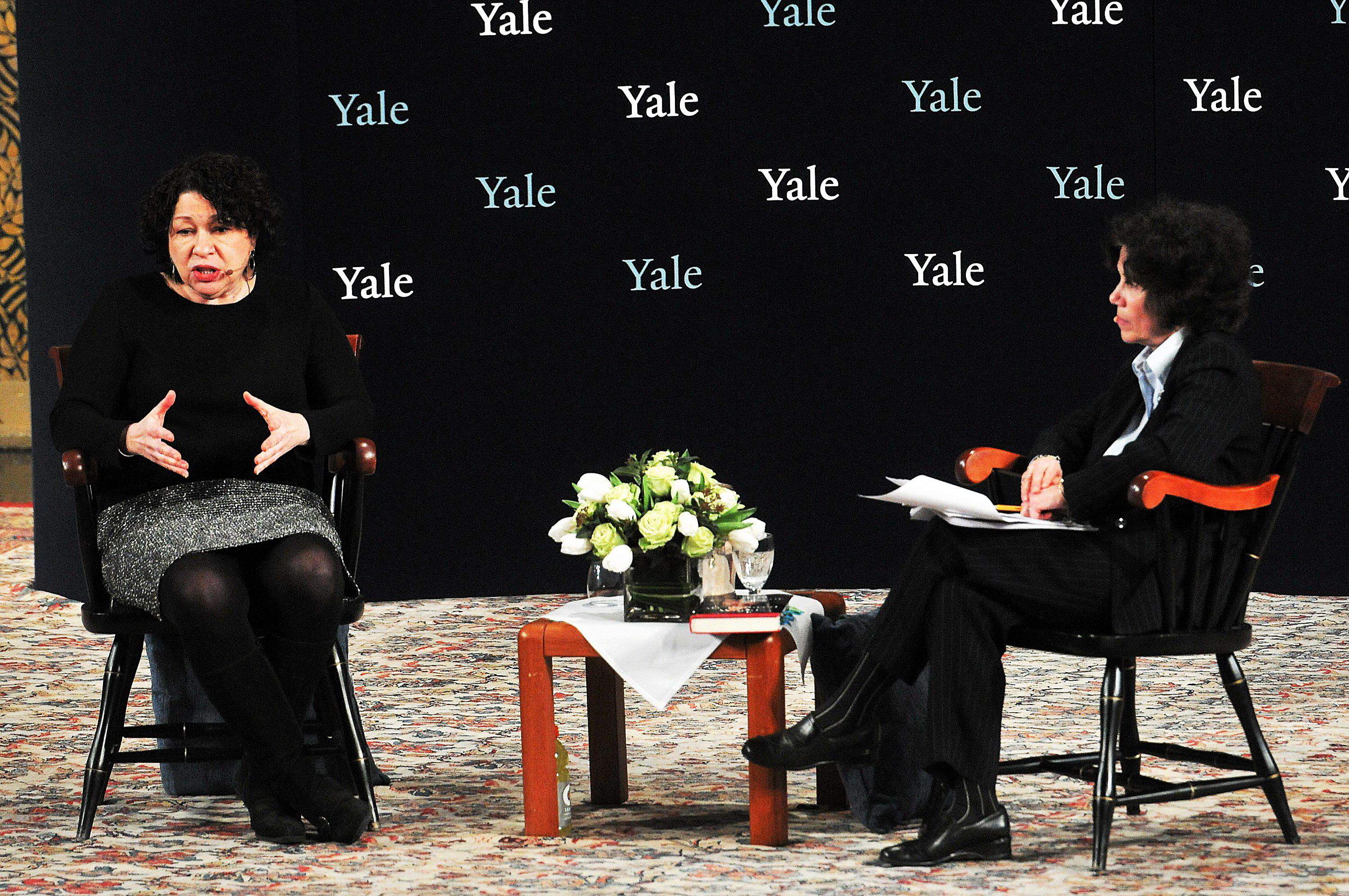

Getty Images

Precisely 12 years ago, a man in Pakistan, with a video camera running to capture the act, drew a knife across the throat of our Wall Street Journal colleague

and murdered him. Danny—gifted reporter, elegant writer, incurable idealist—was a victim of Islamic extremists who either thought he was an Israeli spy or simply liked the idea of killing an enterprising American journalist.

The identity of Danny’s murderer isn’t a mystery, nor is he at large. The Wall Street Journal first disclosed a decade ago that the perpetrator had confessed under interrogation, and more than six years ago, he admitted to the crime publicly. Indeed, he seemed quite proud of his act.

Yet he has never been tried for the crime, or even charged with it.

The confessed murderer is Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, also alleged ringleader of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He sits in prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and it’s unclear when or how he will ever be made to answer for the most horrific death of a journalist on record. And therein lies a tangled tale of the troubled terror-justice system America has attempted to establish after 9/11.

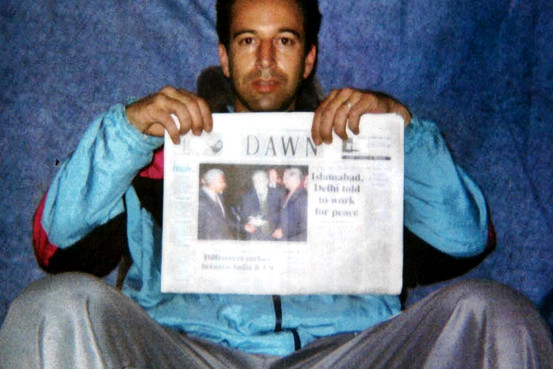

A photo of Daniel Pearl taken by his captors before he was murdered.

European Pressphoto Agency

Mr. Pearl was an India-based correspondent for the Journal when he traveled to Pakistan in 2002 to report an article on the activities of Richard Reid, the “shoe bomber.” While heading to an interview in pursuit of that story—a story that he thought, correctly, might also lead him to groups involved in the 9/11 attacks—he was abducted. His gruesome fate wasn’t known for weeks.

Mr. Mohammed was captured in Pakistan in 2003, not for his role in the Pearl murder, which was unknown at the time, but for his role in planning the 9/11 attacks. He was placed in the hands of the Central Intelligence Agency and underwent harsh interrogation, including 183 waterboardings, in secret detention facilities, according to the government. He confessed to the Pearl murder, a confession confirmed by video evidence.

But he also fell into the war on terror’s justice netherworld. He stayed in secret detention facilities until 2006, when he was sent to Guantanamo. But because of the harsh interrogation he endured, it wasn’t clear that any information or confessions were admissible in court proceedings.

Meanwhile, successive court rulings undercut the military commissions the Bush administration set up, first by executive action and then under a 2006 law. After that law failed to withstand judicial muster, another was written to establish new rules for the commissions in 2009.

The process was sufficiently flawed that Mr. Mohammed and other terror defendants actually tried to plead guilty at a hearing in 2008, but weren’t allowed to do so because the commission’s procedures didn’t allow it. Meantime, the Obama administration tried to move the whole process to civilian courts, but that was a political disaster.

Eventually, Mr. Mohammed was arraigned at Guantanamo in 2012, but only for his role in the 9/11 attacks—and he still hasn’t gone to trial for that. It’s unclear when he will. In short, after well over a decade, the system set up to mete out justice to suspects in the war on terror has simply failed to do that.

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R., S.C.), himself a former military lawyer, argues that the wait has “absolutely” been worthwhile, because it has allowed the government to first take the time it wanted to pursue its top priority of extracting intelligence on terror plans from suspects, something difficult under civilian court proceedings.

“All of these years have borne fruit from him and others,” Mr. Graham says. “We were able to put together the story of bin Laden.”

Now, he says, “the intelligence gathering process is over with for him,” and court proceedings can commence.

In a speech at Harvard Law School in 2012, Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, the man in charge of military commissions, acknowledged that the initial panels were “flawed” but that the new commissions “are fair and…serve an important role in the armed conflict against al Qaeda and associated forces.”

Judea Pearl, Danny’s father, says the family has been told the 9/11 prosecution has to come first, which he accepts.

“We understand they don’t want to interfere with [Mr. Mohammed’s] other trial about 9/11,” he says. But the family also seeks some clear signal that the Pearl murder won’t be left unprosecuted indefinitely.

Mr. Graham offers such an assurance: “I promise them this: The day of justice is coming.”

The Pentagon suggests the same thing: “While the government cannot speak to future prosecutorial and charging decisions that may involve individual accused persons, I hope you’ll note my assurances that no one has forgotten this crime and that justice under law will be pursued however long it takes,” says Lt. Col. J. Todd Breasseale, a Pentagon spokesman.

In truth, though, nobody knows how long that really will be.

Write to Gerald F. Seib at jerry.seib@wsj.com